I.I. The History of Empires

Modern empires, such as the UK, Germany, Soviet Union, US, and China, have historically built their power on a foundation of manufacturing, industry, and energy. While services and the financial industry can temporarily sustain power, long-term dominance hinges on the ability to build modern industrial infrastructure, even for AI supremacy. The Western world's neglect of its manufacturing base over the past 30 years has led to an "existential cross-road" by eroding the very foundation of its historical power.

In this chapter:Foundations of PowerExamples of Empires’ Rise to PowerCorrelation between Power and Abundance

Foundations of Power

Industrial dominance appears to be a necessary condition for all large modern empires built over the past four centuries - it doesn’t guarantee success, but its absence guarantees failure.

Effective public/private institutions, education, financial capital, or favorable demographics matter - but they are precursors that ultimately feed into manufacturing, industry, and energy as the material base of power for modern empires. Military power, shipbuilding capacity or nuclear deterrence also matter, but they are outcomes of industrial power. Industrial dominance is ultimately the chokepoint that matters most.

Services and finance can sustain power temporarily - a real-time case study in many parts of our current Western world. Manufacturing erosion doesn’t always mean immediate decline as finance, services, and power inertia can prolong dominance. In a unipolar globalisation era, such as 1991 to 2008, an empire can survive without deep industrial might by leaning on reserve currency status, financial dominance, technological leadership, and nuclear deterrence, while outsourcing manufacturing to global supply chains. This equilibrium allows service- and knowledge-based empires to “coast” for decades, as the US and UK have. This model produced decades of prosperity, but also deep fragility. When supply chains break, or rivals rise, service-based empires discover how exposed they are to industrial decay. In the long run, industrial and energy production remain the ultimate foundation of resilience and renewal, even if globalisation temporarily masks that reality.

Many argue that the winner of the current age of empires will be determined by AI supremacy, but again, most of the critical components of winning the AI race beyond research talent - scaling energy supply, building data centers, producing chips - are closely linked to the ability to build modern industrial infrastructure.

Rebuilding intelligent real-world infrastructure in the West is not just an “investment thesis”, it’s an imperative to maintain our relevance on the world stage.

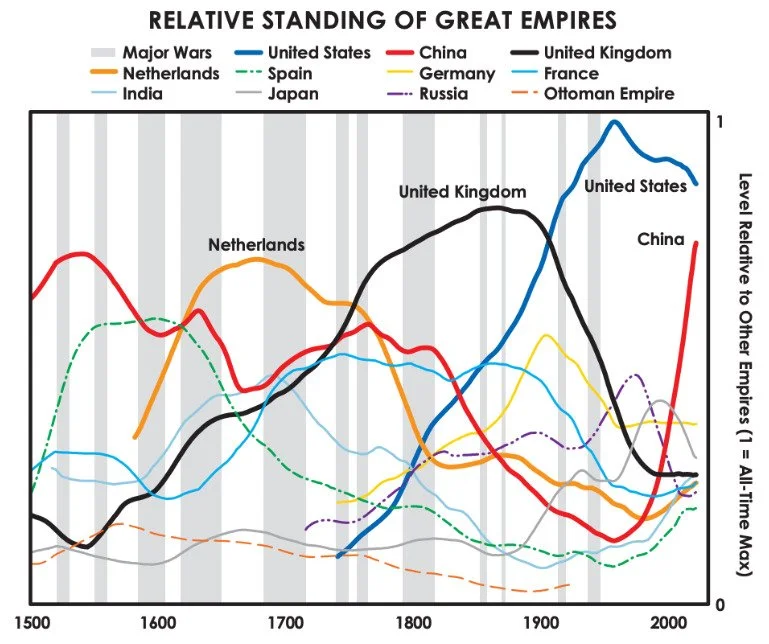

Source: Ray Dalio, The Changing World Order

Examples of Empires’ Rise to Power

United Kingdom – From Industrial Cradle to Precarious Financial Hub

Britain’s empire rested on coal, capital, and institutions. After the Glorious Revolution (1688), secure property rights, Parliament, and the Bank of England created the financial system that funded industry and naval expansion. Coal deposits near ports powered the First Industrial Revolution, as mechanized textiles, iron, and steam engines transformed output.

By the mid-1800s, Britain produced half the world’s coal, iron, and textiles, and its shipyards turned this industrial base into naval supremacy. Exports of rails, locomotives, and machinery spread British influence through global infrastructure. Profits were reinvested, sustaining dominance—until Germany and the U.S. surpassed its manufacturing base by the late 19th century.

Today, Britain retains financial and cultural influence but its industrial core has eroded - still relevant, yet a shadow of its former power. Reliance on finance, services, and soft power without a robust manufacturing or energy backbone leaves it geopolitically light in a world again defined by industrial and energy sovereignty. To secure long-term prosperity, the UK must re-embrace industrialism.

Germany – Eroding Strength of the Trusted Innovator

Germany’s rise after 1871 was driven by state capacity, military demand, education, and industrial specialization. The Zollverein unified its economies, and Prussia’s bureaucracy ensured effective governance. Bismarck’s unification created the centralized state to scale industry, while Krupp, Siemens, and BASF became global leaders in steel, engineering, and chemicals. Military demand - from artillery to optics - spurred innovation, and by 1900 Germany had surpassed Britain in steel, becoming Europe’s industrial leader. This engine powered both world wars, but overreach, resource scarcity, and Allied industrial might brought defeat despite its technical strength.

Today, Germany remains Europe’s industrial core, but strengths in autos, chemicals, and machinery are fading under high energy costs, dependence on China, fiscal restraint, and slow digitalization. Its incrementalism risks missing that new industrial races - compute, AI, and energy scaling - reward disruption and scale, not optimization, leaving Germany and Europe vulnerable to decline.

US – Arsenal of Democracy Turned Uneasy Tech Hegemon

The United States rose from a resource-rich continental power to global superpower through demographics, geography, manufacturing, and a culture of entrepreneurial risk-taking. In the 19th century, rapid population growth and immigration supplied skilled labor, while abundant rivers, coal, and later oil provided unmatched resources. The Civil War proved industrial might decisive, as Northern steel and rail output dwarfed the agrarian South. By the 1890s, the US had surpassed Britain in steel, and by World War I was the world’s leading manufacturer. Its vast industrial base made it the “Arsenal of Democracy” in WWII, producing planes, tanks, and ships at unmatched scale. The Cold War then pushed innovation into aerospace, nuclear, and semiconductors, cementing US dominance through scale, resources, and technology.

The US still leads in aerospace, chips, and AI, but decades of deindustrialization have weakened its middle class and material resilience. The deeper risk is that it acted too late and is now playing catch-up - America knows power depends on energy, supply chains, and manufacturing, yet rebuilding them takes time, while China retains scale and infrastructure advantages.

Soviet Union / Russia – From Global Superpower to Europe’s Adversary

The Soviet Union became a superpower through forced industrialization and state control of resources. Stalin’s Five-Year Plans (from 1928) prioritized steel, coal, and hydroelectric output at immense human cost, while collectivization fed industry. During WWII, factories relocated beyond the Urals mass-produced tanks and artillery - the T-34 became the war’s industrial icon. After 1945, the USSR turned its heavy industry and science base toward nuclear weapons, spaceflight, and aerospace, emerging as America’s rival. Oil and gas exports provided hard currency and energy security, but inefficiency, aging infrastructure, and a failure to modernize or innovate led to stagnation by the 1980s. The Soviet model showed that scale and state direction can build power, but not sustain prosperity.

Today, Russia’s war in Ukraine has revived that dynamic: the economy is re-oriented toward military production, ramping output of artillery, drones, and armor, showing how sustained conflict reduces strategy to industrial capacity. Yet, unlike the USSR, modern Russia depends on imports of chips, machinery, and components - with China now the key enabler, especially for advanced technologies like semiconductors.

Japan – Quietly Resilient, with Modest Upside

After the Meiji Restoration (1868) ended isolation, Japan’s state-led drive built railways, shipyards, and steelworks, imported engineers, and backed zaibatsu like Mitsubishi. Victories over China (1895) and Russia (1905) opened markets and resources, laying the foundation for heavy industry. After WWII devastation, land reform, US market access, and export-led policy powered the 1950s-70s economic miracle. Companies such as Toyota, Sony, and Panasonic mastered lean production and quality control, making Japan the world’s second-largest economy by the 1980s. When its bubble burst, Japan pivoted upstream to machine tools, specialty steels, photoresists, and advanced materials - the deep technologies behind global manufacturing, built on decades of process mastery.

Today, Japan remains central to advanced manufacturing, but aging demographics, energy costs, and risk-averse capital threaten its edge as others scale chips, batteries, and new industrial sectors. The deeper risk is that Japan settles into comfortable stewardship of legacy strengths while others race ahead in scale and new industries.

China – From Low-Cost Workshop to World-Class Industrial Builder

China’s rise since 1978 represents the fastest industrial ascent in history, driven by demographics, export-led manufacturing, and state-guided policy. Deng Xiaoping’s reforms opened the economy to foreign capital and technology while establishing Special Economic Zones like Shenzhen. In the 1980s and 1990s, China became the “world’s factory” for low-cost textiles and electronics, exploiting a massive, disciplined labor force. WTO accession in 2001 accelerated integration into global supply chains, and by 2010 China was producing half the world’s steel and dominated shipbuilding. The 2010s saw a move up the value chain, with leadership in EV batteries, solar panels, and advanced manufacturing under “Made in China 2025.” Export surpluses funded infrastructure, military modernization, and overseas investment. Today, China blends manufacturing dominance with rising technological ambitions, positioning itself as the chief challenger to U.S. dominance. Key risks include slowing demographics and Western export controls.

Correlation between Power and Abundance

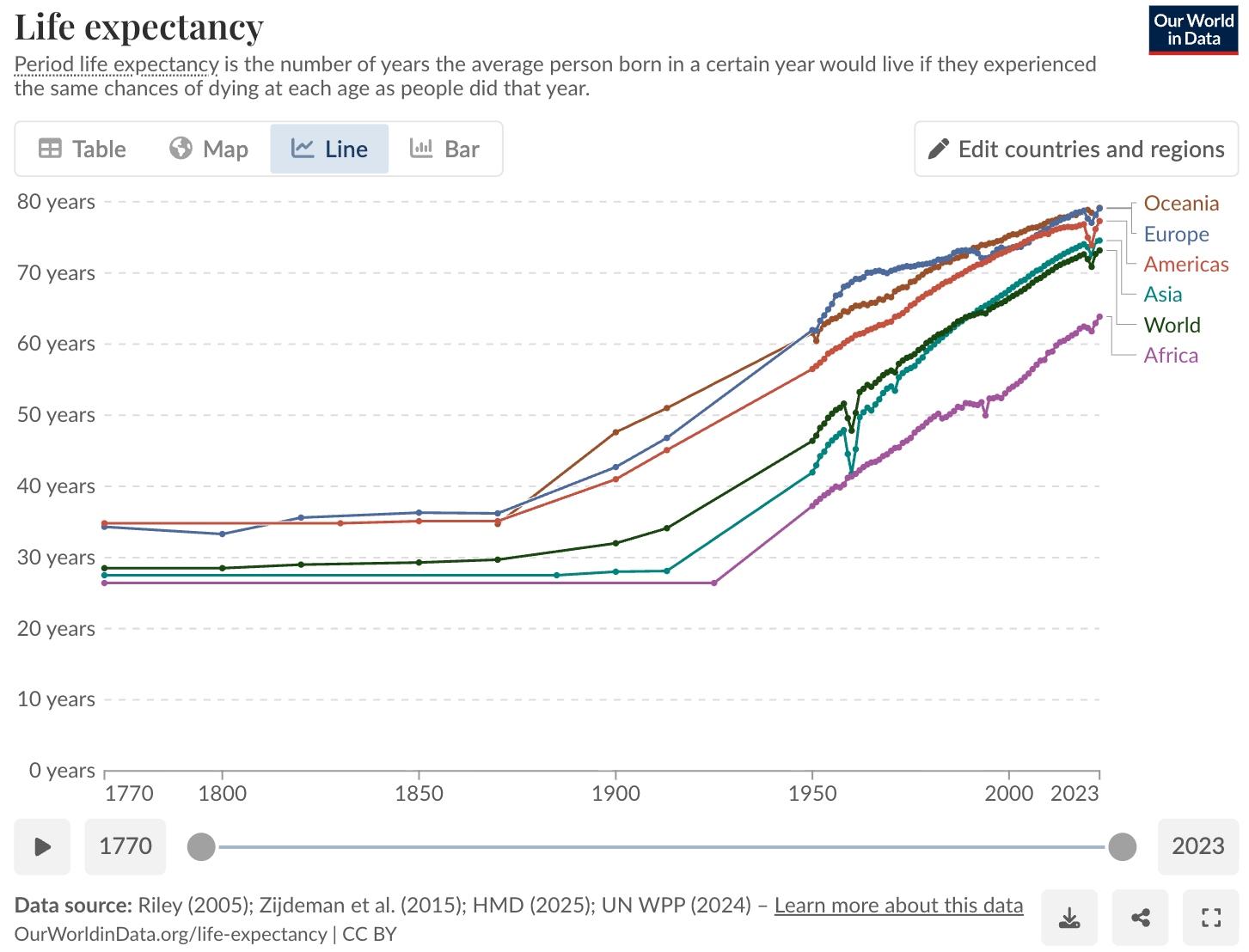

The power of a strong industrial base and energy generation can be clearly seen in data. Britain’s sharp rise in life expectancy after 1870 was the delayed payoff of the Industrial Revolution’s transformation of wealth, science, and state capacity. A century of mechanised production and rising productivity created higher real wages, cheaper coal, and rail networks that stabilised food supplies. Booming municipal tax bases funded vast sewer and clean-water systems, while industrial chemistry delivered affordable disinfectants and soap. The same spirit of applied science that built steam engines and railways also produced germ theory, antiseptic surgery, and systematic vaccination. Mortality from water-borne disease halved between 1870 and 1900, and infant deaths from diarrhoeal illness dropped by two-thirds, driving life expectancy from 40 years in the 1870 to 53 years by 1910.

The 50+ year delay was a product of industrialisation initially worsening urban crowding and pollution, and only once governments and reformers channelled industrial surplus and knowledge into sanitation, housing, and medicine did health outcomes surge, showing how growth’s second-order effects can overturn the externalities it first creates.

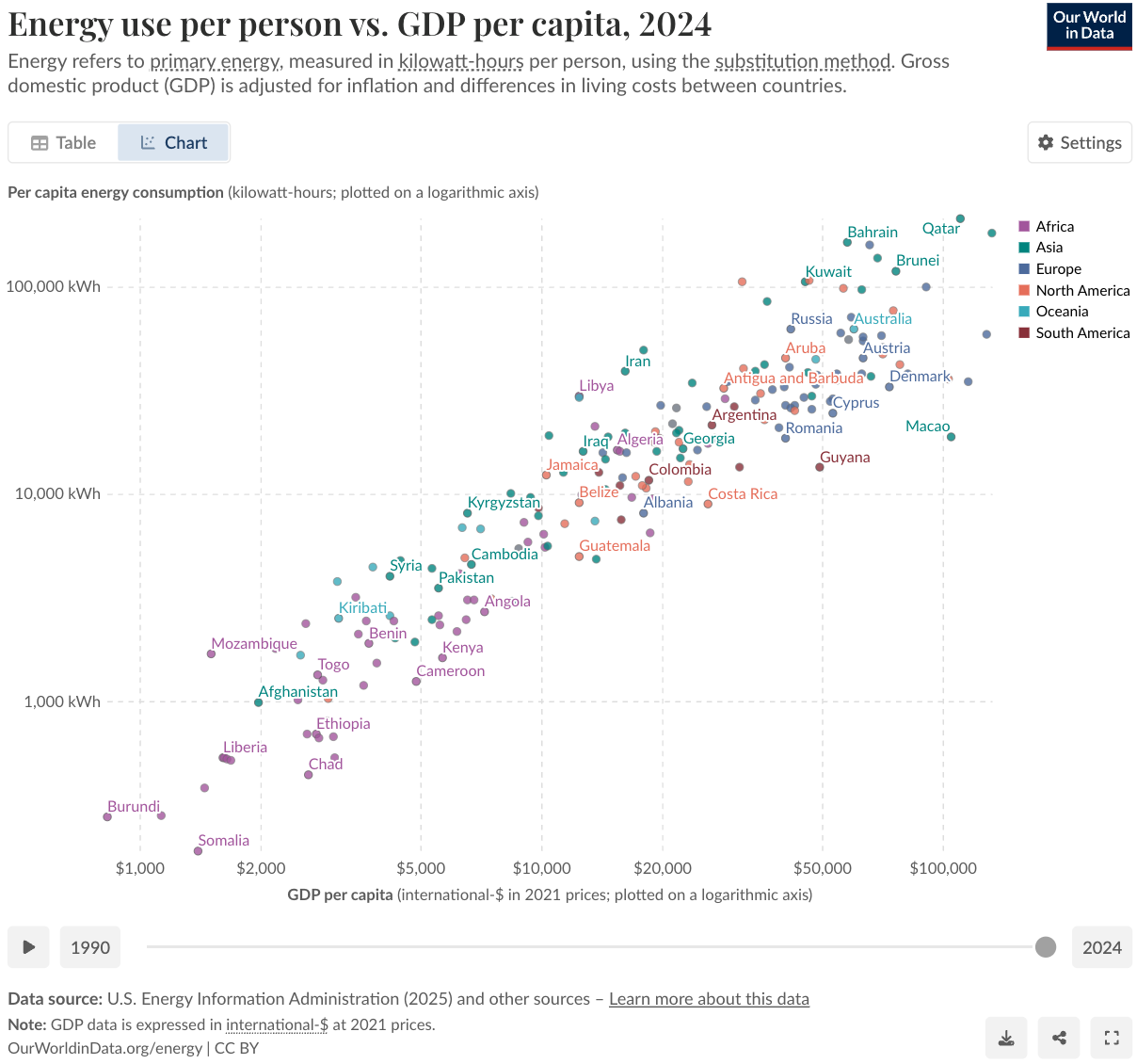

There is a clear correlation between energy use per capita and GDP per capita. Whether this is merely a correlation (“people in rich countries use more energy”) or causation (“abundant energy leads to prosperity”) is still widely debated. Most likely both are true - abundant and affordable energy is a hard prerequisite for industrial growth, manufacturing output, and rising living standards, with the caveat that beyond a certain income threshold, the relationship flattens.

This historical review of empires shows that a robust industrial and energy base seems to form the bedrock of power, a truth temporarily obscured during periods of unipolar globalization by financial and service-based leadership.

The recent de-industrialization of the Western world poses an existential threat to its relevance on the world stage, and requires a proactive and profound modernization of our industrial foundations. This reorientation in strategy and mindset is not just an economic choice, but a crucial step towards ensuring renewed stability, prosperity, and the enduring resilience of democratic principles in an increasingly competitive global arena.

Next chapter: Exploring macro indicators, the world’s transition into a multi-polar configuration, China’s industrial rise in numbers, the West’s will to reindustrialize, and associated roadblocks.

Next Chapter:

I.II. Macro Cycles and The Changing World Order