II.I. The Opportunity - Where I Would Place My Bets Or Build Today

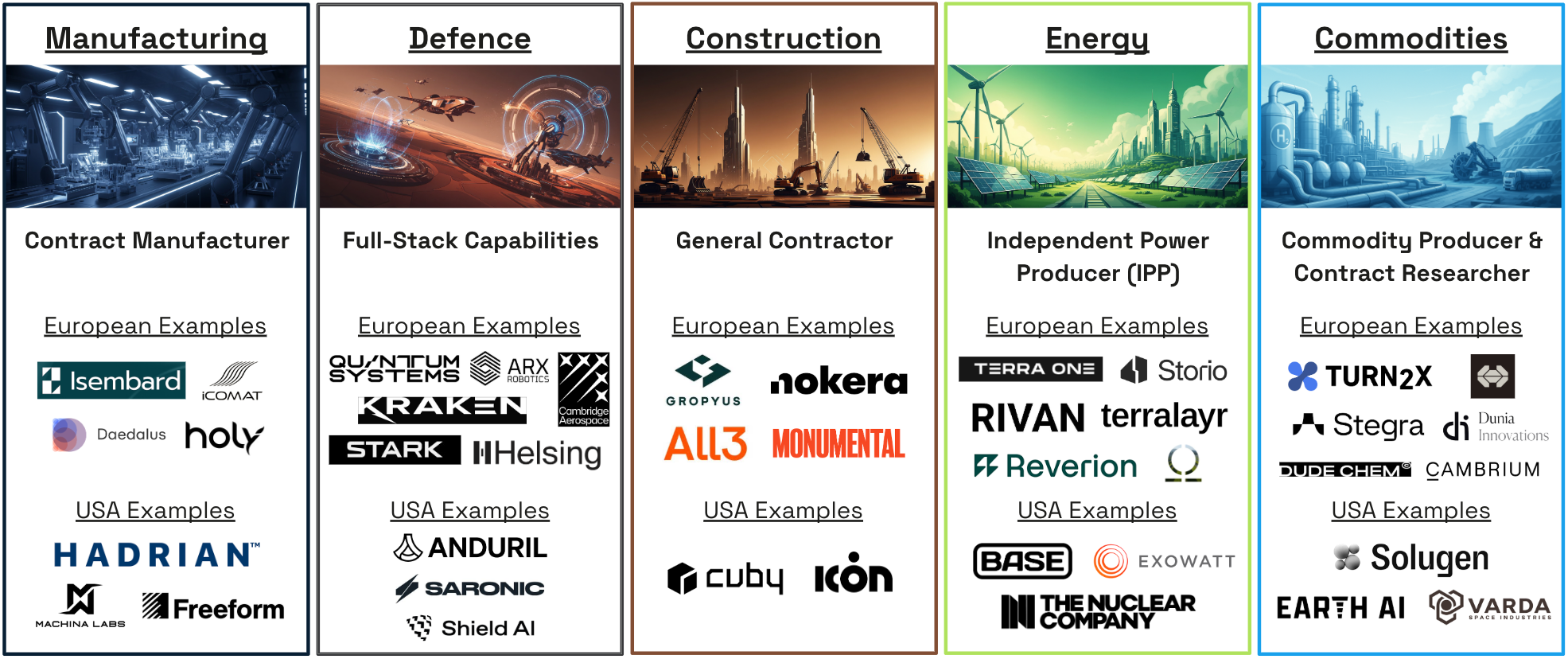

The drivers in previous chapters have sufficiently lowered entry barriers to unlock a Cambrian explosion of Vertical Integrators across five themes where an urgent need and readily available technologies have already converged: Manufacturing, Defence, Construction, Energy, and Commodities.

Their market positioning is similar to incumbents - as contract manufacturer, general contractor or energy provider - selling into existing procurement streams, but delivering a superior product or service across various dimensions.

In this chapter:How the Foundational Principles Fit TogetherManufacturing – Component Contract ManufacturersDefence – Providing Full-Stack Capabilities to GovernmentsConstruction – General Contractors or Specialised SubcontractorsEnergy – Energy (Service) ProvidersCommodities – Commodity Production & DiscoveryHonorable Mentions

How the Foundational Principles Fit Together

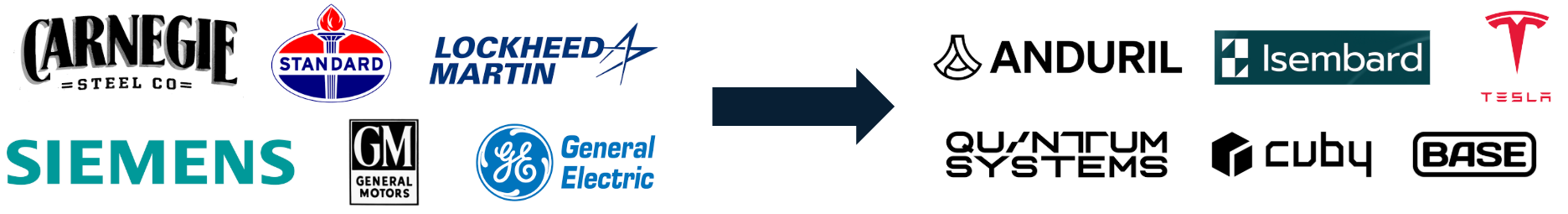

Across two centuries of industrial history, swings between integration and dis-integration have closely tracked shifts in geopolitics and technology. Periods of rivalry, war, or disruptive invention push firms and states to (re-)integrate supply, design, and production of ‘real-world tech’ so they can deliver new capabilities quickly and control risk - from Britain’s 19th-century rail and steel giants, to WWII arsenals, to today’s battery and semiconductor fabs.

In calmer eras, during an era of stabilised, predictable world-order where geopolitical risk is low, industries unbundle into global value chains, optimising cost through specialisation and cross-border scale, e.g. as in post-1970s containerisation or the fabless/foundry split in chips.

The 2020s mark another inflection: pandemic shocks, US-China rivalry, Russia’s war, and the clean-energy race are driving renewed verticalisation/integration, starting with strategic hardware (chips, EVs, defence systems, grid tech, component manufacturing), even as other sectors remain modular. Understanding this rhythm - capability-driven integration in moments of geopolitical upheaval, efficiency-driven dis-integration in times of stability - is key to spotting where the next integration opportunities will surface.

The drivers in previous chapters - both in the macro climate and foundational technologies - have unlocked a Cambrian explosion of Vertical Integrators in the past 2-3 years. Of this first wave of Vertical Integrators, my personal observation is that 90% of the most interesting VIs can be attributed to one of five categories: manufacturing, defence, construction, energy, and commodities.

Some VIs could be categorized into several of these categories. There are often overlaps or blurry lines between manufacturing & defence, manufacturing & commodities, energy & commodities, and manufacturing & construction.

One of the most interesting and attractive traits of VIs is that they sell into existing budgets and procurement streams and replace incumbents, rather than sell to them. Note that the market positioning of many VIs as contract manufacturer, general contractor or energy provider is similar to incumbents, with the key difference being that the VI delivers a substantially superior product or service across various dimensions.

Source: Own Illustration

We will further dig into each of these categories in more detail - before that, I need to clarify some of the patterns I have come across and the definitions I will use. I see most Vertical Integrators manifest in one of two distinct forms:

Production companies: They vertically integrate physical value chains and predominantly innovate along the production process, rather than shipping a truly novel end-product. Their end-products land somewhere on the spectrum between personalised (think CNC-cut precision parts) and commodities (think green hydrogen or rare earth minerals).

Product companies: They design and manufacture novel, software-defined physical end-products (think AI-powered drones). They usually build two or more core competencies, e.g. design of a complex end-product + internalising parts of the production process to substantially reduce BOM/COGS.

A few examples to show the nuance:

Producing quadcopter drones at $2.5k per piece with open interface, built to rapidly scale reliable production → production vertical integrator: the end-product, low-cost quadcopter drones, are essentially commoditised. The core competency lies in producing them reliably and at scale. Various innovations along the production value chain.

Building a family of sophisticated aerial intelligence drones at >$100k per piece → product vertical integrator: Building more sophisticated, interoperable systems. With proprietary AI software features to give the end-user “superpowers”. The different drone types are designed for inter-operability and swarming. A significant part of the production, assembly and testing process is done in-house to reduce COGS and enable faster feedback loops between production and product design.

Producing quadcopters with outsourced supply chain / production → not a Vertical Integrator: neither innovating on product nor production. Might be a good cash-cow for the owner, but not a defensible, innovative, or “venture-backable” business case.

Now let’s dig into the five categories…

Manufacturing – Component Contract Manufacturers

To understand the role of contract manufacturers, it is important to understand that many companies that we think of as “manufacturers” (Rolls Royce, BAE Systems, BMW) are actually predominantly design and assembly companies. They rely on a long-tail of tier-1/2/3 suppliers who produce the product components using various manufacturing methods across machining, additive manufacturing, injection molding, welding, casting, pressing, wire harnessing, electronics, etc.

When companies like Apple, IBM & co talk about “bringing their factories home”, they first and foremost refer to their assembly plants, yet 60-80 % of value in complex products lies in components. These assembly plants require a plethora of component suppliers to build the end-products. The West is steering towards the unenviable position where assembly facilities return to sovereign ground, but the components are still purchased from China, India, and ASEAN, making us feel good about “reshoring manufacturing”, while not actually solving the structural issue.

The component layer of manufacturing is dominated by thousands of under-capitalised SMEs, many running decades-old machines and paper scheduling. Lead times for parts typically run 8-14+ weeks, and in fragmented tier-2/3 supply chains on-time, in-full performance often falls below 65%, with rework or scrap adding further delay. Margins are thin, utilisation rarely tops 60%, and median age of machinists is in the late-40s, with a third already over 55, risking a sharp loss of tacit know-how as retirements outpace apprenticeships.

There’s a plethora of vertical integration opportunities in the industrial supply chain across:

Primary production methods (15+ opportunities): casting, forging, CNC machining, 3D printing, welding, stamping, wire harnessing, coating, power electronics, PCBs, etc.)

Primary production steps (8+ steps): raw materials (ores, metals, polymers, fibers) → refining (smelting, separation, synthesis) → commodities / standardised intermediates → component production (machining, stamping, injection molding, etc.) → sub-/module-assembly → system integration (final product build) → testing & validation → certification.

It’s not a perfect n*n matrix, or 120 opportunities (15 methods * 8 steps) in this grid, but there are probably at least 30 different opportunities to build very large techno-industrial champions within the production-/supply-chain - just like there’s a plethora of large incumbents dominating them today.

I would rank the most attractive opportunities by a formula along these lines: market size * urgency & strategic relevance * productivity and gross margin uplift vs status quo * ability to scale vs capital need * time to market.

We ultimately want to address a large industry that is in urgent need of reinvention, where state of the art technology across software and hardware can generate a significant uplift in unit economics and throughput, that can scale rapidly and relatively capital efficiently while reaching meaningful output within 3-5 years of inception.

A mature layer of vertically integrated component manufacturers would rewire the foundation of Western industry. Instead of shallow reshoring, entire supply chains for castings, forgings, PCBs, wire harnesses, and precision parts would sit inside sovereign, software-defined networks. Plants would operate as “industrial APIs”: predictive schedulers and adaptive robotics expose real-time capacity, quality, and cost curves directly to OEM design environments, making procurement as seamless as cloud compute. Throughput per square metre could rise 2-4x versus legacy job shops, with lead times compressed from 12-20 weeks to <4 weeks, and scrap or rework slashed by 30-50%. This combination of automation, advanced QA, and AI-assisted process control could lift gross margins substantially and create industrial behemoths that rival SaaS-style economics at scale. Final assemblers would iterate products twice as fast, defence and energy programs would source components without fragile intermediaries, and SMEs could tap a shared “component cloud” rather than build bespoke plants, creating a dense, resilient, scalable industrial base.

Example: Daedalus, Freeform, Hadrian, iCOMAT, Isembard, Machina Labs

Defence – Providing Full-Stack Capabilities to Governments

The current Cambrian Explosion is caused by the combination of the broader tailwind of the VI wave, with unique market drivers that cause exceptional pressure on rational buyers with huge budgets.

Global tensions are rising with a widely accepted doctrine in military circles along the lines of: “Europe holds Russia in check and the US focuses on the rising threat from China.” European independence/resilience is becoming increasingly important, driven by the war in Ukraine and the US appearing to become an increasingly more unreliable (or at least internally focused) partner. Global security spending topped $2.6tn in 2024 (+9% YoY).

This means countries need to get their house in order when it comes to defending their countries. Defence procurement today is dominated by slow and inefficient legacy prime contractors. The key role of the prime is:

Being a trusted, reliable partner to government buyers with low risk profile

Integrating various software/hardware technologies into a unified capability

Building/managing supply chains to scale production of the capability.

Defence-related government needs and therefore purchasing is experiencing a seismic shift. Historically, governments and militaries purchased complex, expensive, manned systems in low volume for defence and intelligence purposes from traditional primes. In an era of autonomous intelligence and warfare, governments are increasingly looking to purchase cost-effective, autonomous, inter-operable, unmanned systems in high volume (see UK 20-40-40). This means they need to fundamentally restructure their arsenals. Legacy primes remain essential for highly complex, large systems, such as nuclear submarines, fighter jets, and large warships, but their cost structure, business model (“cost+ contracts”), and acquisition cycles (5-10+ years) are misaligned with domains where sensors, autonomy, and attritable systems evolve quickly - where rapid iteration cycles are required to provide state of the art systems.

Existing primes struggle to serve the demand for these novel systems. It opens up a massive opportunity to new entrants, in particular Vertical Integrators who combine state of the art hardware with intelligent AI software into powerful, yet cost effective systems, which they can manufacture at scale - governments need to buy full-stack capabilities, not just individual technologies.

Rapid iteration pace on the frontline of Ukraine forces militaries to reduce their purchasing cycles from historically 5-10 years between cycles to less than 2 years between cycles, opening the door for new entrants. It is often the case that systems bought today become nearly obsolete within 1-2 years. Therefore, modularity and regular software updates to maintain effectiveness of systems over time are crucial. Having operational credibility of battle-tested products from the Ukrainian frontline is an important proof-point for Western buyers.

Every current and near-term conflict is classified as a “war of attrition”. The winner will be determined by who has:

The most powerful and intelligent, yet cost-effective systems

And can produce them at a larger scale than anyone else

Primes will adapt in some areas, but incentive mismatch (cost-plus contracting, compliance overhead, risk-averse culture, slow iteration) leaves white space for a plethora of new entrants. I believe there are three exciting themes in defense:

Domain-focused product VIs: building a highly curated family of systems within a specific domain or use-case (minimal dual-use). Think aerial intelligence, maritime operations, ground-based robotics, strike drones, counter-UAS, etc.

True neo-/challenger-primes: Core capability is integrating custom solutions for governments. More of a tech-enabled custom service provider - often highly acquisitive (buying smaller companies for tech). Position closest to legacy primes, but run on a modern software/AI stack to provider capabilities 10x faster for 1/10th the cost.

Vertical integrators in the production- & supply chain: contract manufacturing VIs in the previous “manufacturing” category and other dual-use generalists, enabling the domain specialist to scale (also selling into legacy industry).

Category #1 are usually product companies, category #3 are production companies, and category #2 are a mix of the two, depending on the end-product focus.

Every modern conflict demonstrates that outcomes hinge on the speed and cost at which intelligent systems can be deployed and produced/replenished (“wars of attrition”). Verticalised players with deep domain expertise and integrated production loops are best placed to meet that need and build compounding moats, while generic “horizontal” vendors, with non-coherent product families, risk shallow adoption without building the deep tech-enabled core competencies to build powerful systems at scale and become trusted domain experts to governments.

I will dive deeper into all of the above in an upcoming “Defence Deep-Dive” blog post.

Examples: A2I, Anduril, Cambridge Aerospace, Quantum Systems, Helsing, Kraken Technology Group, Rowden, Saronic, Stark Defence, TYTAN, etc.

Construction – General Contractors or Specialised Subcontractors

Attempting to industrialise homebuilding is not a novel idea - many have tried and many have failed (e.g. Katerra, Might Builders, etc.) - most stumbled not because the idea was wrong but because they tried to reinvent methods and supply chains simultaneously and/or attempted to integrate too deep into the raw materials supply chain from day 1, burning capital before reaching cost parity or delivering scale.

The pain is real: Housing has become unaffordable, or ‘cost burdened’, for nearly 50% of US households. Median home prices in the US are 6-7x incomes (vs. 3x in the 1970s), Europe faces shortages in the millions of units, and over 50% of under 35 year-olds spend >40% of income on housing.

Construction productivity has barely grown in 40+ years - while manufacturing output per worker doubled, construction has been flat, leaving an estimated $1.6tn in annual inefficiencies. Projects routinely run 20-40% over budget and months late, with skilled labour as the bottleneck. The average worker is in his mid-40s, one-third are nearing retirement, and apprentice pipelines lag. General contractors scrape by on <5% margins, leaving little capital for digitalisation or automation.

The thesis here is that the recent step changes in both foundational hardware and software technologies - e.g., digital design (BIM, generative layout tools), robotic fabrication, automated QC - finally enable new entrants to industrialise home-building at cost parity and reach escape velocity, especially in markets with high labour cost. Even building something as ‘simple’ as a single family home from scratch to move-in requires 1000s of individual steps that need to become industrialised. A key bottleneck in developed countries tends to be skilled labor. VIs can lower the barrier when it comes to skills and training duration, as well as give skilled workers the context-aware and integrated AI superpowers they deserve.

There’s another version of the output vs method debate here. Method meaning the invention of new construction methods (e.g. 3D printing) and output referring to industrialising existing construction methods.

Here once again I lean towards output over method when it comes to venture-like returns and optimising for building €5bn+ EV outcomes. While inventing new methods is interesting, there are several challenges:

Cost parity: If you can’t build at cost parity or below, you are basically irrelevant and won’t achieve mass adoption. Buyers judge the all-in delivered price of each unit (materials BOM + production cost + shipping + cranage + on-site assembly + prep work + financing + risk contingencies). Buyers - usually real-estate developers or infra investors - are highly price sensitive, as margins are thin. Developing a new construction method, scaling it to industrialisation, optimising it to cost parity and then making the integration successful is close to impossible on venture timelines and without burning 100s of $m.

Regulation & financeability: Certifying a new build method means threading a patchwork of paperwork. US codes vary by state and city, Europe layers EN standards with national annexes and warranty bodies. Even if parts pass tests, assemblies often need new listings, and minor tweaks can restart approvals - detrimental for rapidly iterating startups. Inspectors, lenders, and insurers default to familiar systems, adding cost or delay. International roll-out multiplies the burden. Industrialising existing methods also requires adherence to local code, but at least has more certainty, which can be designed into the system and unlocks faster time to market.

Utilization & end-user adoption risk: Novel methods often need expensive tooling. If you can’t reach 70-80 % utilisation quickly, fixed costs swamp the economics of each building. Adoption is ultimately driven by cost parity and consumer willingness to adopt a new construction style, which comes with some inherent risks. A new build method only scales if people actually want the homes it produces. Even if the VI achieves strong line economics on paper, buyers (or institutional landlords) may hesitate over aesthetics, resale value, mortgageability, or “will it feel weird to live in?”

There are many opportunities across the real estate industry: full-stack single family homes, multi-story framing, specialised construction methods (e.g. brick laying), more traditional pre-fabricated construction for standardised buildings, etc. - all of which individually are $100bn+ opportunities.

If construction VIs succeed, housing delivery would shift from artisanal, fragmented projects to scalable, software-defined supply chains. Homes and mid-rise buildings could be assembled with the same predictability as cars. Digital twins and generative design feed directly into automated fabrication lines, components arrive on-site just-in-time with QR-coded traceability, robotic assembly and AI-driven QC compress project cycles from months to weeks. Cost parity or better unlocks mass adoption, with utilisation-driven economics lifting gross margins from today’s <5% to 20-30% for best operators. Skilled workers are amplified rather than replaced, equipped with context-aware AI that reduces training from years to weeks, while labour bottlenecks fade. For buyers and cities, the payoff is profound: housing supply elasticity returns and affordability pressure eases, scaling throughput by multiples while still customising design at the unit level.

Examples: All3, Cuby, Gropyus, Monumental, Nokera, Onx, etc.

Energy – Energy (Service) Providers

Abundant, low-cost energy is a force-multiplier for prosperity and one of the strongest catalysts of national prosperity. It cuts production costs, unlocks new industries, and widens access to heat, mobility, and compute - whether through renewables, nuclear power, or cleaner hydrocarbons. History shows that cheap, reliable energy can trigger rapid gains in productivity, incomes, and geopolitical weight. In contrast, scarcity or high prices, cap growth and resilience.

Iceland is a poster child for energy sovereignty: Before its build-out, Iceland heated homes largely with imported oil and had a small, fuel-exposed economy. Between the 1940s-70s it switched district heating to geothermal, and by the 2000s its electricity mix was almost 100% renewable (70% hydro / 30% geothermal) with ca. 97% of space heating coming from geothermal today. That abundance and price stability attracted energy-intensive industries, such as aluminium smelters and, more recently, data centres (industrial users consume >85% of Iceland’s power). The result is world-leading per-capita electricity use (47-55 MWh/person), near-zero-carbon power, and the ability to convert cheap local energy directly into exports and high wages.

The policy goal in Europe and the US is similar, but execution is plagued by bottlenecks. The energy transition is fundamentally about re-engineering the energy system to shift from finite, high-emission fossil fuels (like coal, natural gas, and oil) to abundant, low-emission sources (renewables like solar and wind, plus nuclear and emerging tech). The US still draws about 60% of its electricity from fossil fuels, with natural gas alone at 43% in 2024, while the EU has reduced this to around 26% (gas 16%, coal 10%), with renewables at 47%.

A successful energy transition requires addressing a few core elements: generation (scaling clean sources), transmission and distribution (moving power efficiently over distances), storage (handling intermittency / load balancing), supply chains (sourcing materials and tech), and economics/policy (incentives, regulations, and capital flows).

There’s a large opportunity for Vertical Integrators to both load-balance the grid and scale renewable generation sources by using software, AI and state-of-the-art hardware to compress siting, financing, construction, and operations under one modern roof.

They manifest in two types:

Tech-enabled Independent Power Producers (IPPs) for energy infrastructure: build a comprehensive AI software suite to rapidly plan and develop energy infrastructure, such as solar, wind, grid-scale batteries, or even nuclear. At the highest integration level, the VI functions as a next-generation IPP - securing land-use rights through leases, developing and financing projects, and generating revenue by selling electricity into the grid through long-term offtakes or merchant sales. They develop, finance, build (typically via EPC partners), and operate their own assets, with the key difference that they do so much faster, cheaper, and at greater scale, while operating more efficiently and intelligently. They use AI and data-driven strategies to originate advantaged sites, lock permits and grid capacity, structure offtakes and merchant stacks, engineer/construct with standardised hardware, and then operate with proprietary software and AI-powered energy trading. Some VIs monetise intermediate products, selling entire sites or fully developed and permitted (but not yet built) projects. Others integrate into the supply chain of the physical infra they are building. For example, in-housing parts of the design and assembly of their grid-scale battery units.

Product companies: Novel full-stack products for energy generation or load-balancing. Closer to deeptech than traditional Vertical Integrators, e.g. systems with reversible fuel cell technology, that can draw power from the grid and produce green methane during peak power supply times, while switching to electricity generation using the stored methane during times of peak demand. These products can be wrapped by IPP platforms.

Some companies, such as The Nuclear Company or Base Power end up somewhere in between the two. The integration seam is where value ultimately accrues - turning capex-heavy assets into a software-steered, financeable capacity factory.

At scale, energy VIs turn power from a bottleneck into a programmable input. Developer-builder-operator platforms cut development timelines by years, lower capex requirements substantially, and use AI-driven trading and predictive O&M to boost utilisation and margins. Full-stack product companies add long-duration storage and flexible generation, enabling grids to run reliably on >80% renewables. The result is abundant, low-cost, near-zero-carbon energy that anchors re-industrialisation: factories and data centres co-locate with sovereign clean supply, households benefit from lower bills, and nations gain energy security as a competitive edge.

Examples: Base Power, Copower, Exowatt, Factor2, Feld Energy, Reverion, Rivan, Terra One, The Nuclear Company

Commodities – Commodity Production & Discovery

Commodity production - think metals, fuels, or feedstocks - remains one of the least re-architected layers of real-world infrastructure. Mining, refining, and bulk chemical synthesis are still dominated by asset-heavy incumbents that optimize for incremental yield rather than step-change efficiency. Global demand for critical minerals needed for EV batteries, wind turbines, and semiconductors is projected to rise 3-7x by 2040, but permitting for new mines in the US or EU averages 7-12 years versus 2-3 years in China. Refining capacity is even more concentrated: over 80% of cobalt and graphite processing, and ca. 60% of lithium hydroxide conversion sits in China. Despite huge public commitments to “strategic autonomy”, Western supply chains for key inputs remain fragile and import-dependent, while operating margins for many bulk producers hover in the mid-single digits, leaving little room to finance modernisation.

Commodity production is less about automating knowledge work in manufacturing and more about scaling new methods of production to mass adoption, as well as building the data stack, and then the agentic orchestration to maximize the value of agentic process control.

The VIs in this segment ultimately materialise as:

Contract manufacturers for commodities: Scaling mass adoption of novel production methods and designing facilities around connectivity, data, agentic process automation, and predictive maintenance, driving higher quality & scale output at lower energy cost with less downtime → VIs predict up to 15-25% EBITDA margins (vs. 5-10% for incumbents), allowing substantially faster infra build out.

Contract research organisations: A parallel vertical integration opportunity sits not in commodity production, but in commodity discovery - across materials, chemicals, and drugs. Next-generation CROs are evolving into full-stack discovery engines - combining AI-driven molecular design, robotics-enabled high-throughput labs, and advanced analytics. Instead of years of trial-and-error, they run closed feedback loops: models generate candidates, automated labs synthesise and test them, and the results feed back to improve the models. This can cut discovery timelines by an order of magnitude and reduce cost per experiment by 70-90%.

Full-stack industrials (mining, refining, etc.): Scale mass adoption of novel mining/refining technologies, integrating state of the art software & AI tools across the value chain with lean, agentic operations across geospatial AI for prospecting, robotic or autonomous drilling, modular concentrators, and sensor-dense refining lines under a single software/data layer. → targeting up to 18-25% EBITDA margins (vs. 8-15% for incumbents), allowing substantially faster infra build out.

Vertical integrators with CapEx-heavy real-world infra can scale capital-efficiently from an equity perspective through various financial structuring methods that will be covered in Chapter II.II.

Once scaled, these commodity VIs will form the substrate for every other techno-industrial build-out across energy, manufacturing, defence - much as Carnegie Steel or Standard Oil underpinned the Second Industrial Revolution. They will deliver resilient, low-carbon flows of feedstocks, enabling gigafactories, shipyards, and defence primes to source inputs without fragile, scale-constrained supply lines. Price discovery will shift from opaque spot markets to transparent, throughput-driven contracts, with production tuned by AI agents that balance carbon, cost, and quality in real time. For Western economies, success means shortening supply chains, cutting embedded emissions, and building sovereign control over the physical inputs of prosperity. For investors, these platforms combine commodity-like scale with venture-style growth, an opportunity to build enduring monopolies in the most fundamental tier of the energy-industrial stack.

Examples: Cambrium, DudeChem, Dunia, Earth AI, Hades Mining, Solugen, Stegra, Turn2x

Honorable Mentions

Food: Kaikaku

KAIKAKU operates and transforms quick-service restaurants through vertically integrated technology from robotics to AI. They acquire and scale brands, bringing efficiency and loyalty to a highly fragmented trillion-dollar industry marred by 144% labour turnover rate and low profit margins - ultimately giving consumers the experience they deserve and making high quality, healthy food affordable at scale.

Space: Starcloud

Starcloud builds and operates data centres in space through vertically integrated hardware, solar arrays, radiative cooling, and AI control. Falling launch costs, advances in reusable rockets, and cheaper in-orbit assembly now make space-based compute commercially viable. In a world where terrestrial data centres face land, permitting, energy, and cooling constraints, Starcloud offers abundant solar power, natural radiative heat rejection, and uninterrupted uptime. By shifting hyperscale AI training clusters off-planet, they unlock massive compute at lower cost, higher sustainability, and global reach - decoupling digital intelligence growth from Earth’s bottlenecks.

Space: Icarus Robotics

Icarus Robotics is building a robotic labour force for space, combining advanced manipulators, teleoperation, autonomous navigation, and AI-driven control to handle construction, maintenance, and assembly in orbit. Space operations have long been bottlenecked by the cost and risk of astronaut EVA, but falling launch costs, modular satellite design, and robotics now make continuous off-world labour feasible. They start by taking over menial work on space stations and - in the long run - will assemble large structures, service satellites, and prepare lunar infrastructure - creating the industrial labor backbone for the growing space economy.

Vertical Integrators will capture most of the value in the techno-industrial era, much as industrial monopolies did a century ago. Over the past three decades, markets went horizontal - asset-light, demand-driven, focused on scale and cost reduction. The pendulum now swings back: integration is required to innovate physical products, rebuild sovereign supply chains, and restore resilience in the Western world. Aggregators won the internet by owning demand, Integrators will win the physical world by owning supply. Asset-light software playbooks cannot solve asset-heavy real-world problems. The next generation of iconic companies will not enable incumbents, but replace them - building enduring and compounding value by mastering the full stack of the physical economy.

When these integrators reach scale across manufacturing, defence, energy, construction, commodities, and even space, the world will look fundamentally different: supply chains localised and resilient, energy abundant and cheap, housing affordable, critical industries sovereign, and space travel a routine. In short, a re-industrialised West, powered by software-defined physical systems, with prosperity and security rebuilt on a new foundation of vertical integration.

Source: Own Illustration

Next Chapter: Addressing common misconceptions about Vertical Integrators.

Next Chapter:

II.II. A Wildly Misunderstood Category