II.II. A Wildly Misunderstood Category

Vertical Integrators are often misunderstood and mislabeled - especially in Europe. They’re dismissed as too capital intensive, hard to scale, misaligned with VC timelines, unpredictable in revenue, valued on low multiples, or lacking defensibility because they rarely start with deep IP moats. While there are failures that reinforce these fears, treating them as universal truths is as misguided as claiming “SaaS doesn’t work because of high churn.” In practice, most of these concerns are overstated and there are clear mechanisms to solve them. The mistake is in treating these challenges as fatal flaws, rather than design constraints that can be overcome. Fine distinctions matter: capital intensity vs. dilution, recurring vs. predictable, scalable vs. exponential, margin vs. value capture.

In this chapter:Capital Intensity vs. Equity IntensityExit/Liquidity Options & Valuation MultiplesVenture Backable: Scalability within VC Fund CyclesRevenue PredictabilitySize of the Opportunity

Capital Intensity vs. Equity Intensity

Packy McCormick and William Godfrey have covered this topic at length in their great “Capital Intensity isn’t bad” post. I’ll pull some excerpts from their work and add some of my own thoughts and frameworks.

“While hard tech startups, or Vertical Integrators, can require more capital than software startups, those capital needs don’t necessarily translate into more dilution for equity investors. In fact, hard tech startups that master structured finance achieve lower dilution than software companies burning equity on customer acquisition.” (Not Boring, 2025)

Capital intensity does not equal equity dilution - the concept that really matters to investors and founders to protect their upside. The best Vertical Integrator founders are obsessed with the cost of capital - a concept most people in the innovation ecosystem seem to forget after their last economics class in high school / uni - these VIs leverage the right source of capital for the right purpose.

Real-world Vertical Integrators (RWVIs) have the unique benefit of building and owning real-world assets and can rely on “old economy” financing structures to scale them - project finance, asset-backed loans, etc. Some folks are also building unique capital structuring solutions to marry the best of old & new world to provide tailored financial products to VIs - see Brett Bivens or Oliver Beavers.

The biggest mistake a RWVI can make is continuously using VC-funded equity $$ to buy CapEx assets.

I’d like to introduce the term “equity intensity” for Vertical Integrators instead of capital intensity - the amount of equity capital required and therefore dilution caused until a company can either reach break-even or solely raise non-dilutive capital. I’m pretty sure many successful VIs would fare better at scale when it comes to “equity-intensity” than asset-light SaaS.

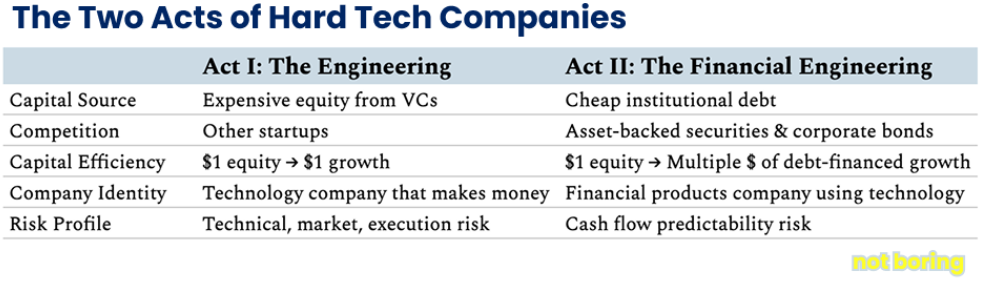

Packy McCormick uses a nice 2-Act framework for hard-tech companies:

Act 1 - The Engineering: Hiring the team, proving the model. “Design the hardware. Prove the technology works. Find product-market fit. Show unit economics. Get to repeatability.” Usually means opening up an R&D facility/factory or a first-of-a-kind (FOAK) site - it requires some CapEx, but I have seen 6-month-old startups get up to $1m+ in asset-backed debt from state-sponsored banks to outfit their R&D site with machinery (usually via industrial SMB incentive schemes). This phase is where VIs tend to burn a lot of equity if they are not careful - staying nimble is key. In most cases it doesn’t take a team of more than 15-20 FTEs to test the hypothesis, build the R&D site and make the model work. Any non-deeptech VI worth their salt should be able to traverse this phase with less than $10m equity raised.

Act 2 - The Financial Engineering: Once the model, technology, and demand are proven, Vertical Integrators can often rapidly scale to 10s of $m in revenue - often at 30-60% gross margin - in the first 12-18 months of proper commercialization. It’s not uncommon to suddenly see them reach profitability only 3-4 years into their journey. Continuously building out real-world infra at scale requires lots of capital, but with clever financial engineering, VIs can leverage various forms of debt and revenue-share based business model innovations (e.g. franchising) to rapidly scale with minimal equity dilution. “Act II is about turning your deployed technology into a financial instrument that institutional capital wants to own. You're no longer asking investors to underwrite your startup risk. You're asking them to underwrite the cash flows your technology generates.”

Source: Packy McCormick, Not Boring

I have met several VIs, without being able to disclose names, who have burned less than $25m in equity, reached the inflection point and likely never have to raise a cent of equity again, while being on track to reach 100s of $m in revenue within 5-7 years of inception.

What also tends to be quite capital- and equity-intensive is proper deeptech (material science, fusion, etc.), especially deeptech combined with vertical integration in the delivery. That’s one of the main reasons for my “output over method” argument in Chapter I.III. - These companies often require $100m+ in equity financing to develop, industrialise, and then scale their proposition. Some can soften the blow through customer- or government-funded R&D, but dilution tends to be high nonetheless with substantially greater risk in execution.

There are some unique business models I’ve come across to elegantly incentive-align the scaling of real-world infra with low equity-intensity:

Cuby’s SPV model: Cuby industrialised homebuilding - they’re a construction Vertical Integrator to build single family homes for the masses. The thoughtfulness of their approach and technical depth are impressive and only matched by their acute awareness of cost of capital. They deploy small- to mid-sized factories all over the US. Cuby finances each Mobile Micro-Factory (MMF) through an SPV with local developer partners (or industrial family offices) who put up the required upfront capital, while Cuby builds and operates the factory itself. The partners benefit from access to predictable, low-cost housing supply, while Cuby scales faster with less balance sheet strain and captures ongoing upside through factory operations and software integration as a license fee. Often, the local partner also takes the majority of the factory offtake. In practice, this materialises as the investor financing the majority of the upfront CapEx with a subsequent leveraged revenue share between Cuby and the investor. As the model becomes increasingly proven, project finance for the factories becomes available and the equity required reduces significantly. (Packy also wrote a fantastic deep-dive on this mutual portfolio company here - Cuby: The House Factory Factory)

Isembard’s franchise model: Isembard builds component manufacturing factories to reindustrialize the West - their product are full-stack, small- to medium-sized, highly efficient, software-defined factories for component production, such as CNC-machined precision parts. Their proprietary AI platform, MasonOS, automates everything from quoting and scheduling to robotics and production, enabling a single factory to run at 2-3x the output of traditional shops, serving defence, aerospace, and wider critical industries. To unlock non-linear, capital efficient scaling, Isembard leverages franchising to create a network of factories, scaling faster and cheaper than traditional incumbents. They reap many of the benefits of vertical integration - building modern, highly standardized and controllable sites from scratch - while leveraging the franchisee’s equity buy-in and SBM loan to finance the vast majority of upfront CapEx required for each site, with the added benefit that factories can be rapidly deployed within 1-2 months - much faster than their “gigafactory” counterparts. The franchisee owner-operator also serves as a “complexity-absorbing” layer when it comes to operational discipline and quality control. The owner-operator has a much higher interest/incentive to “run a clean shop”, than a factory manager on a $60k salary. Lastly, lowering the entry barrier to the manufacturing industry for a new wave of entrepreneurs, will draw a massive wave of talent into the industry, which is ultimately needed to make a dent in the macro-context of the industrial base. In short, the unique model enables Isembard to scale faster and cheaper while reducing key bottlenecks in quality control and talent constraints.

Customer- / Government-funded R&D: The company gets paid upfront by a customer or public agency to develop a product they want, rather than financing that development with investor equity. It’s powerful because it simultaneously reduces technical risk and proves demand before the product even exists. Customers fund this because they urgently need the solution built, and co-developing with a specialist is often faster, cheaper, or more strategic than building it internally - just as NASA did with SpaceX, effectively underwriting reusable rocket development while securing a better launch provider.

Ultimately, “The future belongs to companies that combine the world's best engineers with the world's best financial engineers.”

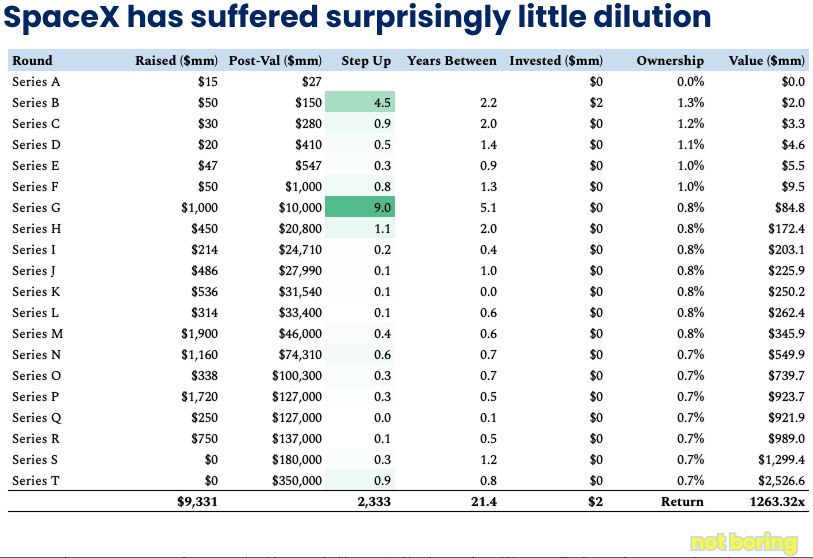

“SpaceX, now America’s most valuable private company at over $350 billion, has also been among its most capital intensive. But, and this is the big one, its fundraising hasn’t been particularly dilutive. SpaceX has experienced less than 50% dilution since its first outside funding two decades ago.” (Not Boring, 2025)

Source: Packy McCormick, Not Boring

“SpaceX has raised over $9 billion in venture capital and growth equity over its life. Uber raised $15.9 billion before going public. It doesn’t take less money to make rockets than it does to make a ridesharing app. The difference is, as The Washington Post reported in February, as if it were a bad thing, that SpaceX has received over $22 billion from the government”. (Not Boring, 2025)

Combine these government R&D and production contracts with substantial FCF from their high-margin revenue streams, such as Starlink, and the low “equity intensity” in terms of dilution doesn’t come as much of a surprise anymore.

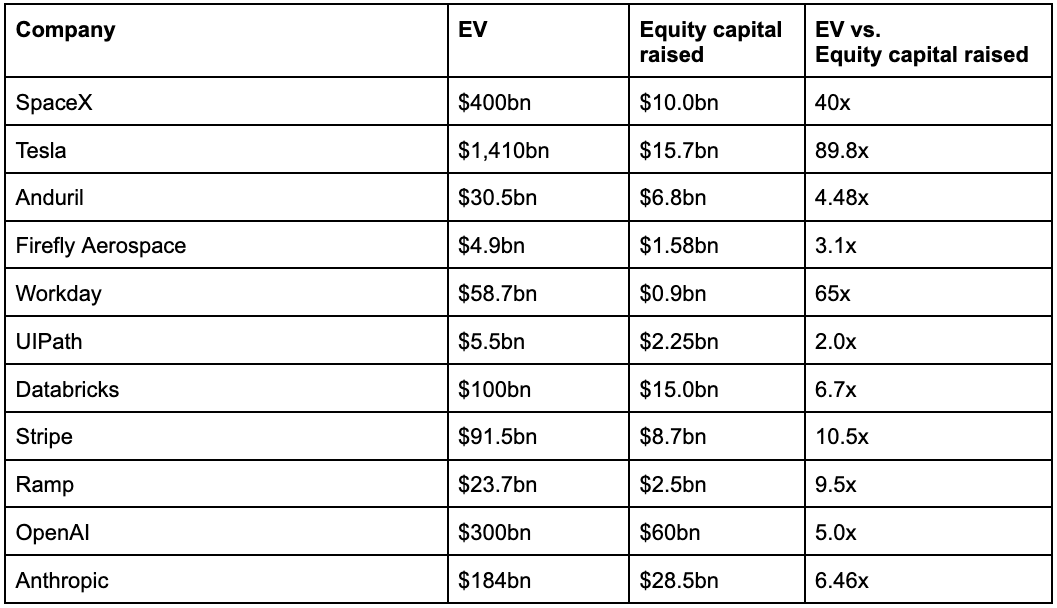

Source: Own Illustration

There are obviously a plethora of factors that influence the “EV vs equity capital raised” metric - this is just to illustrate that many world-class Vertical Integrators can outperform top SaaS/AI companies in terms of equity capital efficiency.

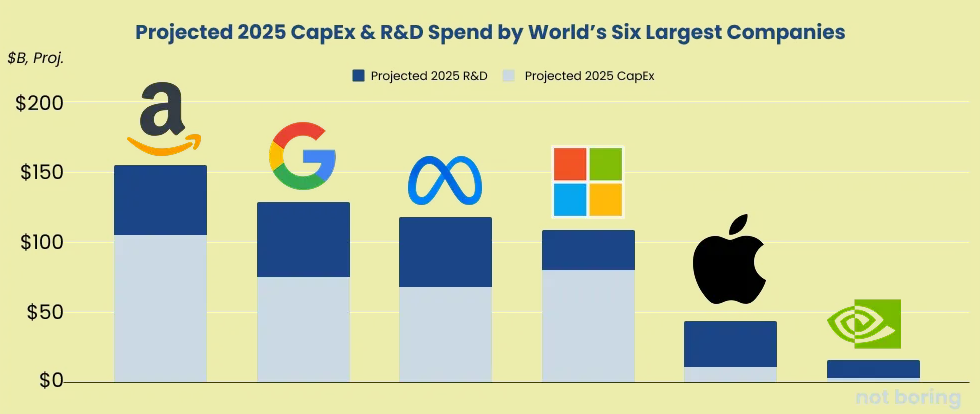

Another interesting phenomenon is the evolution of companies like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft. Once the poster children of asset-light software and consumer platforms, they now deploy tens of billions annually into data centers, custom chips, and logistics. They fund this CapEx from massive free cash flow, balancing reinvestment with buybacks and dividends.

The result is a structural shift: the most valuable “software” firms are becoming industrial giants, vertically integrating into compute, energy, and supply chains to secure long-term dominance in AI and cloud.

This asset-light to asset-heavy playbook working out is likely the exception to the rule. Only very few achieve such scale and the integration was more a necessity or to maintain relevance and defensibility in a more competitive and commoditising arena, rather than a strategic masterstroke planned since the early days - it took 10-20 years of compounding to make that math work. Today’s playbook for VIs should usually be physical infra integration from day 1.

With the important caveat, that the real VI lesson isn’t “go all-in on owning asset-heavy from day one,” but “own critical bottlenecks and value creation opportunities early, rent commodities, and sequence integration as learning curves and demand density justify.” These ultimately economics choices, not ideology, is what made these asset light software firms industrial and why the new generation of monopolies should integrate from day one.

Source: Packy McCormick, Not Boring

In SaaS, the main drain on early cash flow isn’t physical assets but customer acquisition. High upfront CAC, long payback periods, and heavy spend on sales and marketing mean companies must finance growth with equity, since banks won’t underwrite loans against intangible customer contracts or churn risk.

The result is that “asset-light” SaaS is often very equity-intensive. Founders and early investors absorb dilution to subsidize growth, often for a long time, until recurring revenues compound.

Vertical integrators have access to a very different financing stack. They require equity for the initial team and technology build out, but the vast majority of their cash burn comes from rolling out plants, machinery, and working capital, which are tangible and financeable with debt, leasing, or project finance. This makes them capital-intensive but not necessarily equity-hungry. Once the core model is proven, debt can shoulder the bulk of the load, allowing equity to play a more leveraged role and ultimately resulting in lower dilution for equity holders.

Exit/Liquidity Options & Valuation Multiples

A common debate is exit options for Vertical Integrators and how they will be valued. There are widely accepted heuristics for pricing of SaaS liquidity events based on scale, unit economics, growth & co, giving a high degree of comfort to investors that they will be able to generate liquidity in their investments within their time horizons in a relatively predictable price range.

Most VCs don’t have much experience with M&A or IPO transactions in old-world industrials. There is a long history of industrial monopolies being acquired, merging, going public, doing share buybacks or otherwise providing liquidity options to shareholders and therefore a comprehensive set of comps data. I suspect many VCs don’t feel comfortable with the category, because the valuation dynamics differ from their SaaS benchmarks. Undoubtedly, industrial incumbents will fetch much lower revenue and EBITDA multiples than a modern SaaS company. But just because Vertical Integrators replace industrial incumbents, doesn’t mean they will be valued as one, especially when it comes to top-line revenue multiples.

Vertical Integrators tend to be priced somewhere between asset-light SaaS companies and incumbent industrials when it comes to multiples on revenue or EBITDA. VIs command a premium over legacy industrials, as they tend to have higher growth, higher gross margin, better EBITDA margin and other efficiency metrics, as well as higher defensibility in technology and ability to more rapidly expand into adjacent verticals to further drive TAM and compounding at scale.

VIs - on average - tend to be priced lower than pure-play SaaS companies, as SaaS often has higher gross margins, lower distribution cost at scale, lower OpEx, and longer, predictable subscription revenue streams.

Shareholders in Vertical Integrators have four major liquidity options:

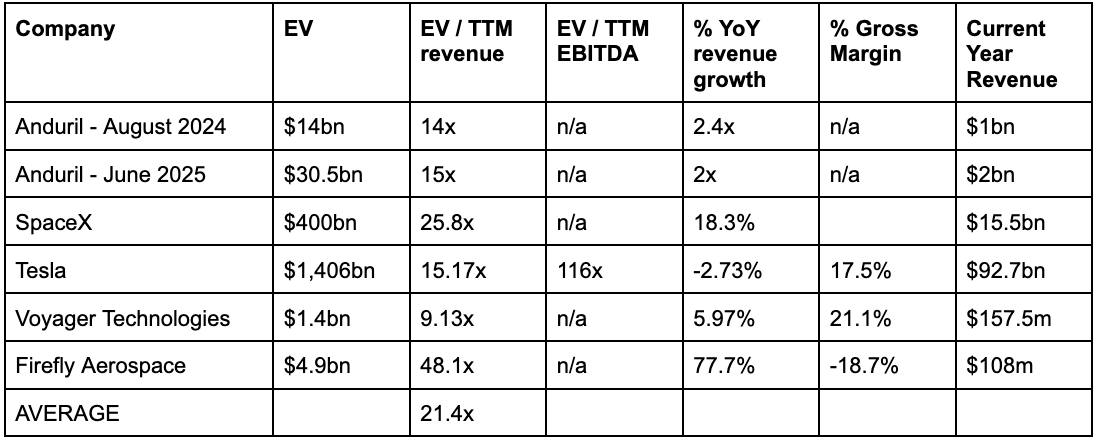

IPOs: Examples like Tesla, Voyager Technologies, or Firefly Aerospace show that public markets can reward techno-industrials when growth, vision, and defensibility align. While less frequent than in SaaS, IPOs remain a credible path for VIs with scale and compelling narratives. Voyager Technologies IPO’d only 6 years after their founding date ($1.5bn valuation). Firefly IPO’d after 8 years ($8.3bn valuation).

M&A: Industrial strategics in defense, aerospace, and energy have a long history of acquiring challengers to fill capability gaps. Multiples may be lower, but these exits can be sizable and strategic buyers are well-capitalized. Large M&A transactions of modern VIs are still outstanding, but large players like Anduril/Helsing are becoming increasingly acquisitive - also lots of interest from incumbent primes (e.g., L3Harris’s acquisition of Aerojet Rocketdyne for ca. $4.7bn in 2022; AeroVironment’s acquisition of Arcturus UAV in 2021 for $405m).

Secondary Market: Liquid and deep-pocketed secondary markets enable category leaders in particular to stay private for longer. Private liquidity events, as seen with Anduril or Shield AI, let early shareholders sell stakes without a full exit. This option has become more common as patient growth equity, sovereign wealth, and late-stage crossover investors actively build positions in (future) category leaders (e.g., Anduril saw over $1.25bn in secondary bids, offers, and transactions activity, in the 90 days around its June 2025 round, according to PM Insights' secondary market data.)

Share Buybacks: Mature, cash-generating VIs can create recurring private liquidity for shareholders through buybacks, making this a viable alternative to public listings. Players such as SpaceX offer share buyback periodically, at least every 6-12 months, with some tenders exceeding $500m, offering even large institutional investors liquidity.

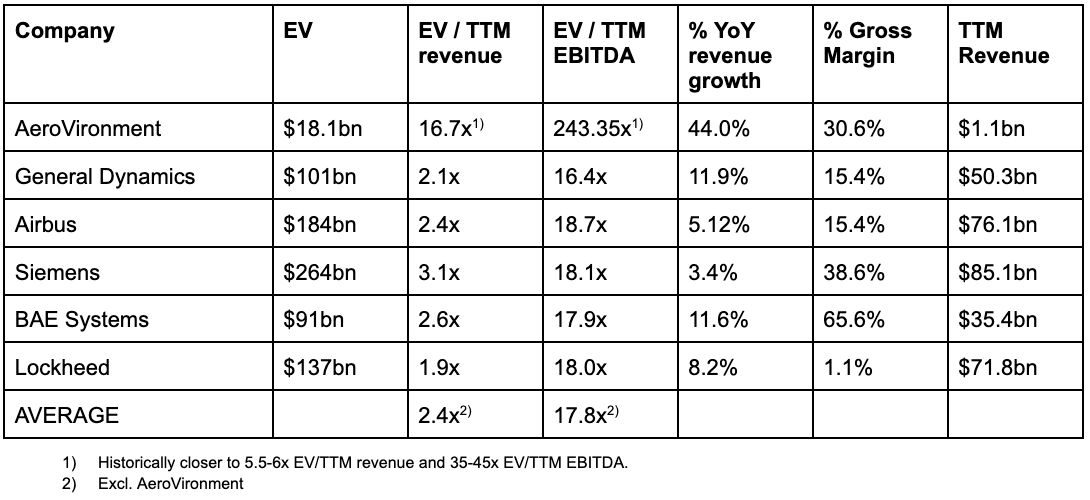

Incumbent industrial & defence comps tend to be value around 2-6x TTM revenue and 16-19x TTM EBITDA:

Source: Own Illustration

Category-leading Vertical Integrators tend to be valued at 10-25x TTM revenue.

Source: Own Illustration

Venture Backable: Scalability within VC Fund Cycles

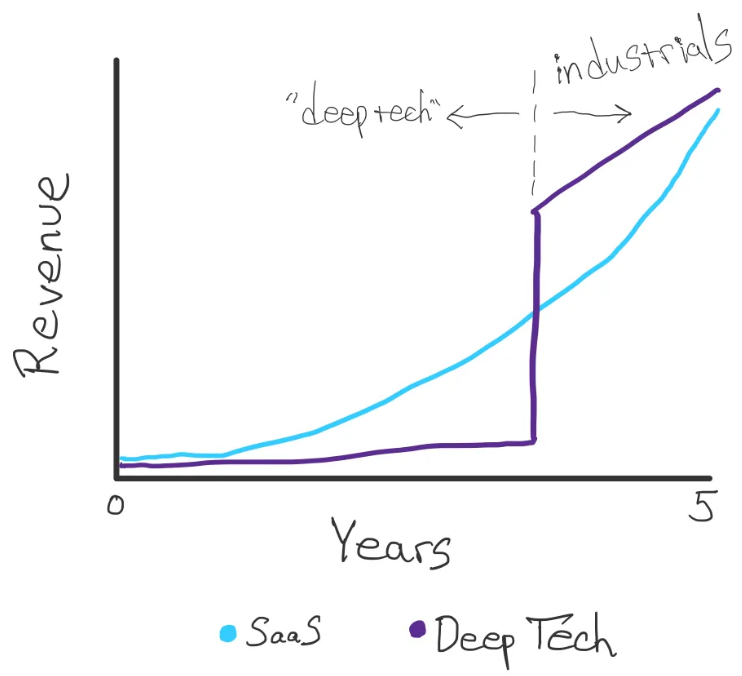

Depending on the level of technical depth, most successful VIs I have met, started with a 2-3 year development phase, to build the team, tech and prove the model. Some were already generating early revenues or unlocked R&D grants from governments or customers, but the revenue in these first years tends to be negligible.

Once the model is proven, VIs tend to scale rapidly, often reaching 10s of $m in revenue in their first year of proper commercialization. This is often driven by:

Low market / adoption risk: They replace an existing, well-understood input in a supply chain, so customers don’t have to change behavior and adoption is frictionless. Even incumbents are incentivized to switch when cost or lead-time savings are obvious - they are usually very rational buyers.

Step change in UX: The product or service is not a marginal improvement but a clear leap forward in performance, reliability, or accessibility. This makes the purchase decision less about persuasion and more about catching up to a new baseline. The output of the VI is often a “no brainer” to buy vs existing alternatives in the market.

Demand overhang: Customers have often been desperately waiting for a better solution. Once the VI proves feasibility, backlog converts almost immediately into orders. This pent-up demand can generate explosive first-year growth.

Large budgets: VIs usually sell into industries like aerospace, energy, or infrastructure where procurement budgets are measured in millions or tens of millions, not thousands.

I’ve come across a number of VIs that manage to reach $30-50m revenue in their first year of commercialisation and then continue to compound at a >2-3x YoY growth rate for years.

Assuming a 8-10 year holding period for a VC fund, and an initial tech development period of 3 years, with $30m revenue in year 4, followed by 3x growth in year 5 ($90m) and 2x growth in the following 3 years, the VI would reach $720m revenue in year 8 once the exit window opens. As demonstrated above, category leading vertical integrators are often valued at >10x revenue multiples, but even a more conservative 4-5x revenue (vs. 8-12x for SaaS) would generate venture-grade returns. The $720m TTM revenue at 4-5x revenue multiple, would fetch a $2.9bn to $3.6bn valuation, and potentially even >$7.2bn at >10x revenue multiple, which should make most early investors very happy, esp. if equity dilution during the hyper-scaling phase is low.

Lastly, VIs often compound at high growth rates for much longer, driven by the massive size of the market that VIs operate in and the size of the budgets, making customer acquisition at scale more efficient and scalable.

Source: Ian Roundtree

Revenue Predictability

SaaS became the VC gold standard because subscriptions offered high margins, low churn, and predictable renewal cycles. But the AI wave is eroding those assumptions: many AI companies operate at 20-40% gross margins and rely on the hope that compute costs will fall enough to eventually reach SaaS-like economics.

At the same time, many of the fastest-growing AI scaleups often suffer extreme churn with month-one retention as low as 50% and 10-30% monthly logo churn - driving a growth model dependent on aggressive nonstop top-of-funnel spend rather than customer retention and expansion.

Vertical Integrators don’t rely on monthly renewals. They lock in revenue through long-horizon commercial and government contracts. These agreements typically include multi-year terms, milestone or progress payments, minimum-volume or take-or-pay commitments, and indexation to FX or input costs. Many also include year over year expansion options and the installed base often converts into high-margin aftermarket revenue from spares, servicing, and upgrades.

The result is 12-36+ months of contracted visibility, minimal default risk, and cash flowing early in the delivery cycle, which reduces working-capital needs even if reported gross margins look lower. By contrast, SaaS often burns capital to constantly reacquire churned users or acquire smaller ACV customers via expensive performance marketing. VIs can achieve far greater customer-acquisition efficiency by winning a small number of durable, high-value contracts instead of thousands of short-lived subscriptions.

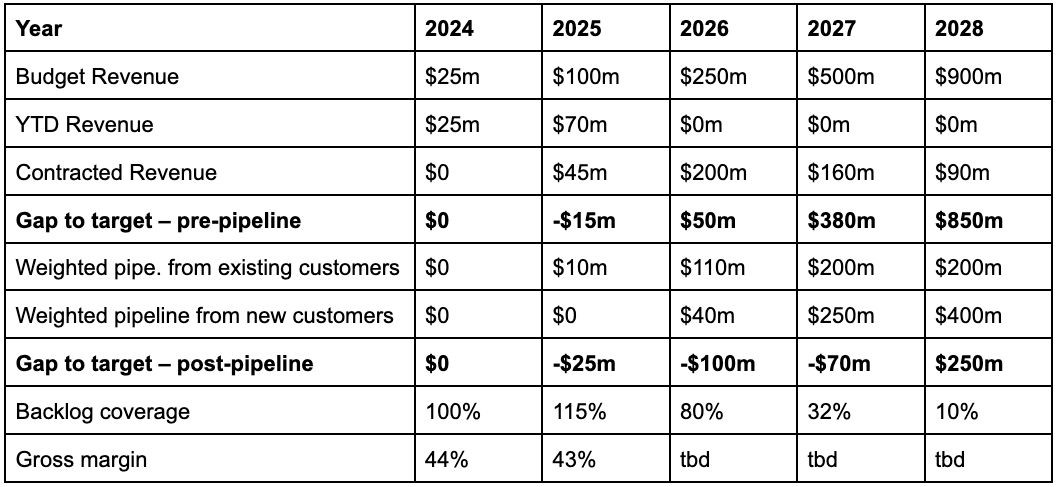

The reporting for a Series B/C stage Vertical Integrator could look something like this (as of Sept 2025):

Source: Own Illustration

Most of the next 18 months revenue is well-covered by contracted (to be delivered) revenue with strong visibility and coverage in the weighted pipe to achieve budget until EoY 2027.

A crucial milestone for a VI is expanding beyond prototyping or POC orders. Once the VI wins large contracts, they often become a trusted, sometimes even exclusive supplier for certain product lines for governments or tier-1 OEMs - as long as performance is satisfactory. They can often grow into 8-figure, or 9-figure contracts within a single customer.

That being said, VIs carry their own risks: Customer concentration, budget cycles, termination rights, delivery/acceptance milestones - but these risks are usually legible and hedgeable via diversification across programs, termination fees, indexation, and service mix.

Bottom line: In a world where “recurring” revenue can be an illusion, Vertical Integrators often offer equal or better predictability - rooted not in vibes or vanity ARR, but in contracted backlogs with credible customers who rarely churn and often scale. It’s not as perfect as “old school ARR”, but it provides sufficient predictability to scale efficiently.

Size of the Opportunity

There are two critical misunderstandings in the size of the opportunity:

Underestimating how large a single vertical integrator can become

Undercounting how many “niche” industrial seams can support one with $50-100bn+ potential outcome size.

Every time I think I have mapped out the Vertical Integrator opportunity space (see chapter II.I.), I come across a new theme, where a creative, hyperambitious entrepreneur goes after another $50bn+ opportunity in a “niche” segment of the industrial base - most recently, that was in the testing, inspection, and certification domain.

Why there are more VI opportunities than expected:

Industrial “niches” are actually massive: Many categories that look small from a software spend lens sit on multi-billion system budgets once you include hardware, labor replacement, compliance, and lifecycle costs (TIC is a classic example).

Budget migration tailwinds: Reshoring, reliability, and safety push spend from opex (manual, fragmented, multi-vendor coordination) to capex (automation + integrated providers, single-point of accountability), expanding the addressable pool for full-stack offerings.

Capex-as-distribution unlocks scale: Milestone/prepaid contracts and public funding reduce go-to-market friction and finance capacity, letting VIs scale into markets that software alone can’t unlock. When attaching to massive CapEx, even a minor uplift in value capture as part of the total spend can mean millions in increased gross profit for the Vertical Integrator.

Spec power creates category power: When a VI writes the spec and controls interfaces, it effectively defines the market boundary and therefore its own TAM (e.g. SpaceX with the Starlink satellite bus and launch stack, or Tesla’s NACS charging standard).

VIs often address opportunities that are orders of magnitude larger than the respective SaaS TAM or their beachhead market. Tesla is not ‘just’ an automotive company. They started building EV sports cars for the 0.1% of the population, then they expanded into the affordable EV mass-market, then batteries, clean energy, and humanoid robotics, etc.

VIs have a lot of optionality to radically expand their TAM, and getting those bets right is crucial.

Why single-VI TAMs get mis-sized:

Re-bundling beats point solutions: VIs collapse fragmented stacks (design → make → integrate → service) into one accountable vendor, capturing system budgets rather than line items. That shifts the TAM from “software spend” to the customer’s full workflow spend.

Stack adjacencies compound: Winning the beachhead unlocks upstream (materials, components), downstream (installation, O&M), and lateral (testing/certification, training, software) steps - often via natural pull from customers. TAM grows with each layer absorbed, not capped at the beachhead. Each additional adjacency is easier to absorb once the VI controls the spec and interfaces.

Bottleneck ownership becomes a toll: Control over regulated steps (e.g., testing, inspection, certification) or safety-critical integration turns into durable pricing power and pull-through demand for the rest of the stack.

Learning-curve scale effects: Process IP, automation, and procurement leverage push unit costs down over time (Wright’s law). As costs fall, the VI can expand from premium segments into mass-market and infrastructure - while widening moats and making it harder for competitors to catch up.

Installed-base flywheel: Once assets are deployed, the VI earns recurring revenue from maintenance, spares, upgrades, data, software layers, or even financial products. Over time, the aftermarket can outweigh the original sale and lock in long-term customer dependence.

What still surprises me is how often investors reflexively underestimate these outcomes.

The emerging playbook for Vertical Integrators is to capture three things:

The bottlenecks (so value flows through them),

The learning curve (so cost, speed, and data compound in their favour) and

The spec/interface (so others must build around them).

Once those are in place, the ceiling stops looking like a niche and starts looking like a massive industry.

Vertical Integrators aren’t just defensible, they can even be financially superior in ways most investors overlook. Despite being capital-intensive, the smartest VIs are low in equity-intensity, using debt, project finance, franchises, SPVs, or customer-funded R&D to scale with little dilution. Their exit paths are diverse across IPOs, strategic M&A, deep secondary markets, and even recurring share buybacks. Valuation multiples already sit between SaaS and industrials, with category leaders trading at 10-25x revenue. They scale fast, often hitting $20-50m revenue in year one of commercialization, backed by multi-year contracted income rather than leaky ARR. The real upside is that even “niche” industrial seams can hide outcomes in the 10s of $bn for those who control the bottlenecks, the learning curve, and the spec.

Next Chapter: Exploring some of the key risks that could shrink or delay the Vertical Integrator Opportunity.