I.III. Why Vertical Integration Is Necessary to Drive Systemic Change

The industrial saviors of Western societies will look more like the monopolies built during the Second Industrial Revolution, than the software companies of the past three decades. They deliver physical end-products by integrating complex, fragmented value chains, combining cutting-edge, but largely proven hardware technology, robotics, and AI software. Their leverage comes from designing physical infrastructure around software and AI to drive a meaningful step change in efficiency and scalability. They ride exogenous technology curves to build products that naturally get better over time - obsessing with execution speed and balancing invention with pragmatism.

In this chapter:Why Vertical Integration Is NecessaryDefining “Real-world Vertical Integrators” (RWVIs)Anecdote: The Relationship between Application-layer SaaS Products and Foundational ModelsWhy Output over Method, and Balancing Complexity MattersAddressing the Labor ConstraintUnderestimated TAM for Vertical Integrators

Why Vertical Integration is Necessary

Complex value chains, especially in the physical world, optimize for reliable throughput above everything else - in an assembly- or production-line’s throughput is ultimately rate-limited by its slowest station.

Applying a single innovation in software or hardware to a production line can, in theory, deliver a major productivity leap. In practice, the gains are usually modest. Even if a new technology targets the current bottleneck, overall throughput soon becomes limited by the next constraint elsewhere in the value chain.

While I use an assembly-/production-line as an example here, the same principle applies to most complex physical value chains.

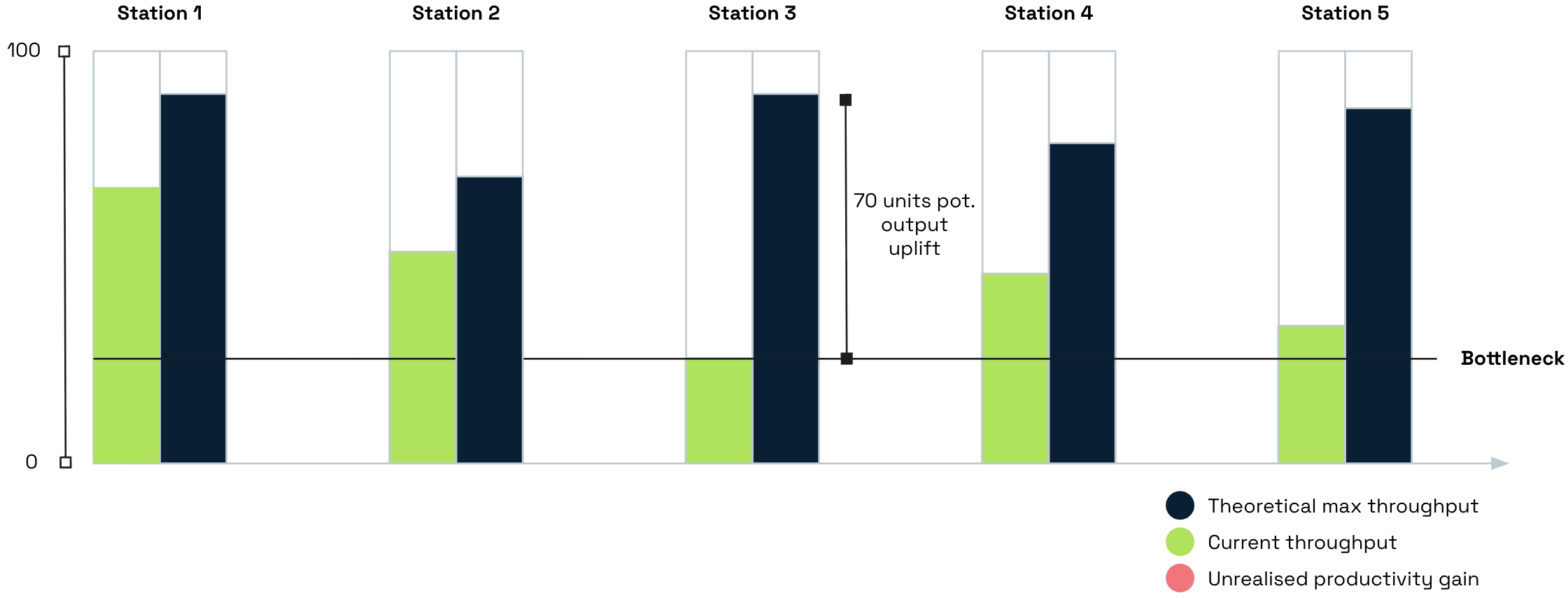

Consider the hypothetical production line with five stations below. Let’s say station 3 is quality control and the current bottleneck. We now find a computer vision solution in the market that could, on paper, increase the throughput in quality control from 20 units to 90 units per hour.

Source: Own Illustration

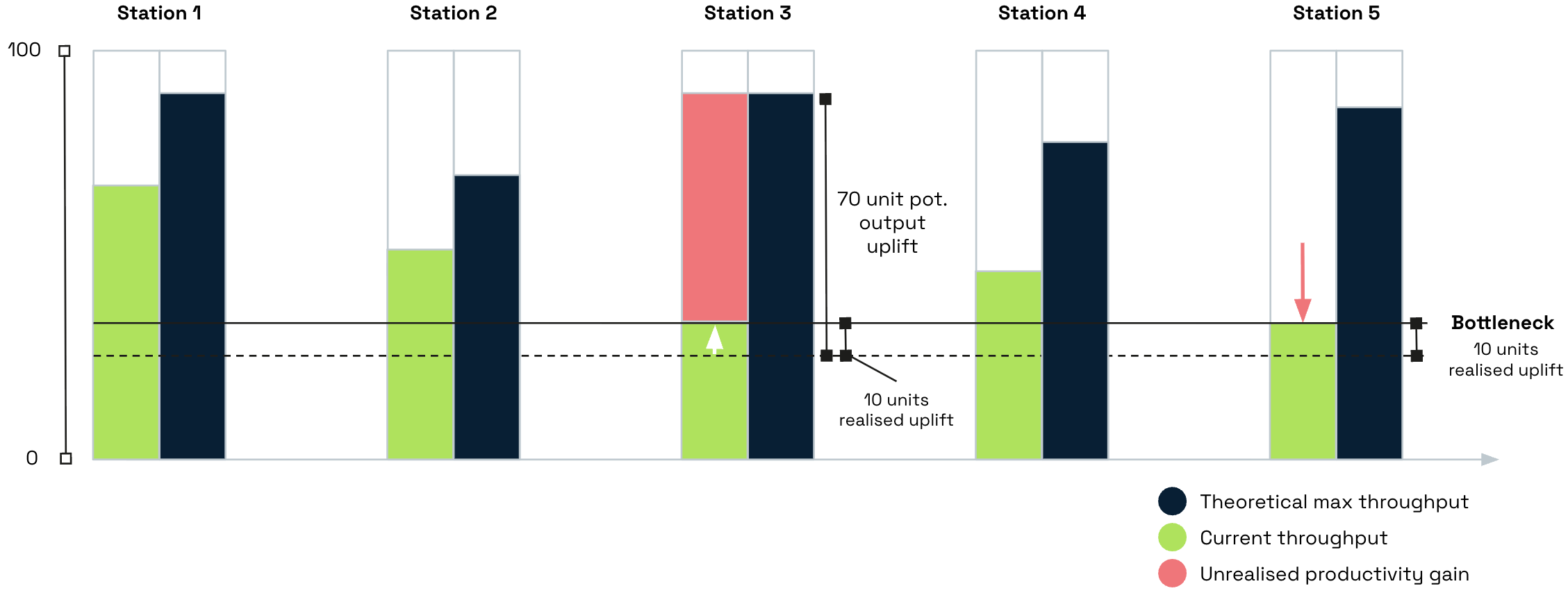

We apply the technology, but the realised output increase across the value chain is only 10 units, because the bottleneck jumps from Station 3 (quality control) to Station 5 (let’s say packaging & shipping).

Source: Own Illustration

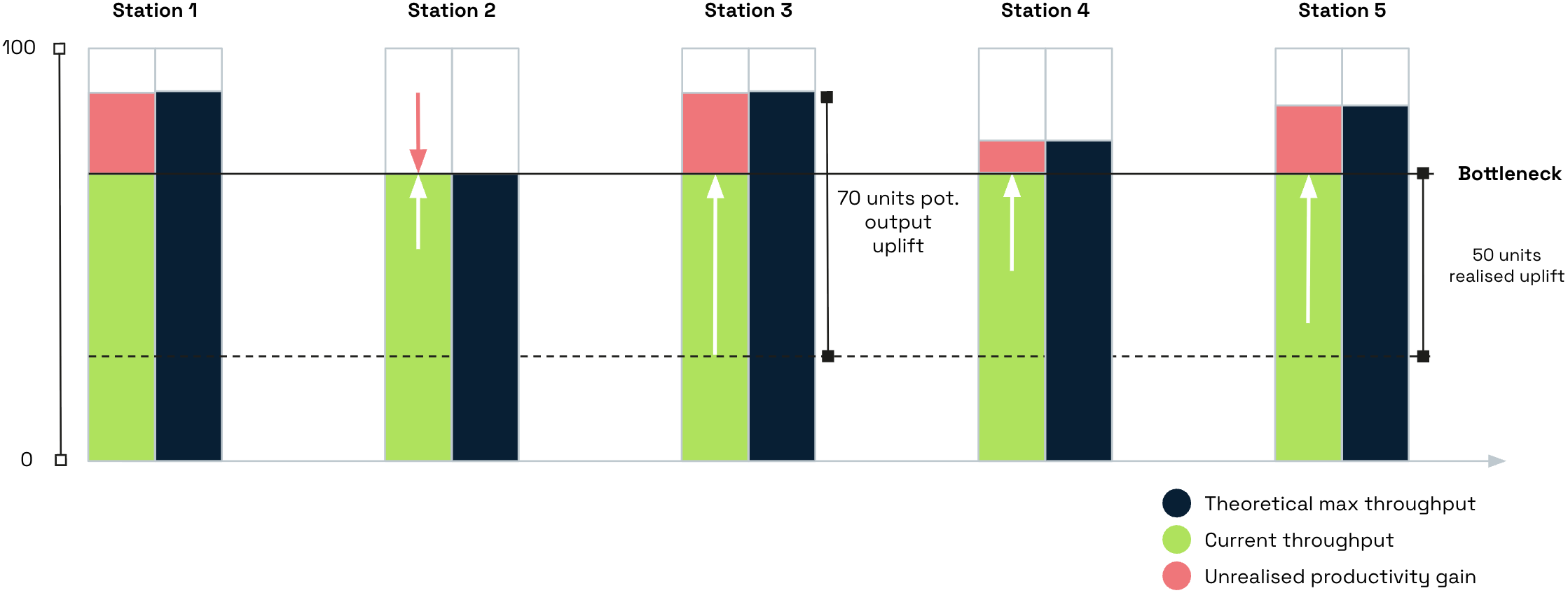

To drive a true step-change in throughput, various proven, state of the art technologies have to be applied across the entire value chain, jumping from bottleneck to bottleneck. This unlocks a throughput increase as close as possible to the theoretical maximum. In the example below, applying various technologies across the value chain unlocks a throughput increase of 50 units per hour across the production line - a game changer and significantly more powerful than the 10 unit increase of the single technology.

Source: Own Illustration

Of course, industrial incumbents are already running these iteration cycles, but they are slow and struggle to innovate or properly adopt new technologies. New entrants can start with a clean sheet, design their facilities to gain maximum leverage from the current state of the art solutions, implement best in class technologies without technical debt and jump on bottlenecks across the value chain at breakneck speeds.

These future leaders won't just bolt on trendy AI or robotics to existing lines. They'll seize control of fragmented value chains, knitting together hardware, software, and automation to unlock throughput bottlenecks. Real gains demand vertical integration, where an AI-native company doesn't just experiment with one technology but relentlessly upgrades each link, chasing the true limiter of efficiency.

Only by owning the chain can Vertical Integrators spot where off-the-shelf tools hit their ceiling, then innovate and increasingly build their own proprietary IP to unlock leaps others miss. Obsessed with output over inventing new methods, these vertical integrators treat exogenous tech curves as accelerators: adopt proven robotics or AI fast, swap them out when better arrives, but only if it kills the current bottleneck.

This approach also enables the modern real-world vertical integrator to collect large, domain-specific, and highly contextual datasets, which they can leverage to train proprietary AI models to further drive efficiency across the value chain.

Most importantly, their leverage ultimately comes from designing physical infrastructure around software and AI. Not layering SaaS onto existing processes, but rebuilding from first principles - where data, automation, and control loops are embedded from day one, built for scalability.

Defining “Real-world Vertical Integrators” (RWVIs)

Vertical integration is a spectrum - rather than providing an ironclad definition of a RWVI, I will instead list a number of characteristics that I associate with a RWVI. If most of them hold true, chances are the company is a RWVI in my book.

A RWVI…

Delivers a physical end-product, capability, or service, while capturing a significant part of its value chain.

Combines cutting-edge, but largely proven hardware technology, robotics, and AI software to drive a meaningful step change in efficiency and scalability in a complex, physical value chain.

Rides exogenous technology curves to build products that naturally get better over time and act as ‘GTM channels’ for mass adoption of new hardware technologies in the physical world.

Directly competes with incumbents, rather than selling software / products to them.

Closes real-world feedback loops to build unique data assets and subsequently train domain-specific AI models.

Can relatively quickly reach a dominant market position and build a massive moat, while capturing a much larger piece of the TAM. Compared to pure-play SaaS companies, they’re not a COGS item for the legacy player, but capture the entire gross margin themselves.

Ultimately, they look more like the monopolies built during the Second Industrial Revolution at the end of the 19th and start of the 20th century, than the software companies of the past three decades.

RWVIs don’t have to be deeptech companies! (arguably better if they’re not)

A deep tech company designs a product for optimal performance, taking on the risk of unproven science or technology to do so, while a Vertical Integrator designs a system for optimal performance, taking a risk on the combination of proven technologies.

For the Vertical Integrator, the integration itself is the innovation.

Example: Quantum Systems doesn’t build new motors or battery packs. They design, manufacture, and distribute sophisticated drones composed of powerful, proven, off the shelf components.

Anecdote: The Relationship between Application-Layer SaaS Products and Foundational Models

AI-native application-layer SaaS startups ride the exogenous technology curve of foundational models, i.e. if a newly released LLM is 2x better, by whatever metric, you should plug it into your existing SaaS product and leverage the technology to improve your existing product.

In the early days of the GenAI wave, when investors were trying to figure out where to place their bets, a common razor to make investment decisions was: Is the founder excited or concerned about a 10x improvement in foundational model performance? Does a 10x improvement in foundational models improve your product or make it obsolete?

It’s not a perfect metaphor, but I think there are many parallels to real-world vertical integrators: “Does a 10x increase in a technology along your value chain excite you or make you obsolete?”. Invest in the former.

Why Output over Method, and Balancing Complexity Matters

Building Real-World Vertical Integrators is hard - founders are dealing with complex, physical value chains and there are good reasons for many bodies along the way over recent decades. On the flip side, if they can make it work and deliver a step-change in productivity, throughput, quality, and scalability, the payoffs are massive - shortest past to deeply defensible, industrial monopolies.

One of the big questions I have been pondering about over the past years is the sequencing of output vs IP, or innovating on output vs method.

Take the example of a contract manufacturer in composites. You have two options:

Output first, method second: Start by integrating state of the art, proven technologies. Build your first facilities, scale output. Once you’re scaling and the true rate-limiting bottleneck becomes obvious, start innovating on method. If the ‘final’ or ‘residual’ bottleneck after applying available technologies across the value chain is the actual production machine in fiber-placements, start innovating on your own, proprietary machines. If it’s in testing, start to build IP and proprietary machines there.

Method first, output second: Start by innovating a new production technology, e.g. a new method of fiber placement in additive manufacturing. Invent the new method, scale it to the output required to industrialise it. Then vertically integrate and set up your own facilities around the novel production method. These are often referred to as “deeptech” companies, because they generate IP early.

My bias is toward option #1 - “output > method” - with the caveat that my focus is building/backing tech startups capable of reaching $5-10bn+ in EV within 8-10 years, ideally 100s of $bn. Method-first companies more often end in sub-scale or strategic exits - still meaningful, but rarely transformative.

That being said, vertical integration only generates venture-grade outperformance when it removes real fragility, enables capabilities that modular suppliers can’t deliver, or creates a true step change in end-user experience/economics. Otherwise, it's just cost, complexity, and distraction dressed up as strategy.

“Output over Method” is an argument to not get stuck in lengthy and costly R&D for years without real customer feedback.

Why “method first, output second” or “method > output” vertical integrators tend to fail:

Fundraising cycles & time to market: Building a vertical integrator by itself is already a big challenge. Inventing a new production methods and driving it up the TRLs (technology readiness levels), then further scaling it up to reach the required output for industrialisation - often requires and increase of 10x to 100x in production speed - and then making the integration successful, all within venture-cycles and usually within the timeline of one or two rounds of funding (i.e. 18-36 months) is close to impossible and more often than not results in sub-scale exits, if at all.

Concentrated IP / competency: The vast majority of the moat or core competency is in one technology (e.g. the new production method). That also means they’re one foundational scientific breakthrough away from becoming obsolete - e.g. if someone else develops a faster/better method. That is not the case for the full vertical integrator.

Team: The founder/team profile required to invent a new method and the founder/team profile required to make vertical integration work is vastly different. The former is much more technical and domain-specific. The latter is more about being able to deal with huge amounts of complexity and moving fast with rapid iteration cycles.

There are always exceptions to the rule, but my personal razor is: If you’re inventing a new production technology, and that’s your core competency, monetise it as such. Sell production cells or licence it, don’t fully vertically integrate.

The only scenario I can see option #2 (method > output) work is if the leap in method is so massive and defensible, that it puts the company into a de-facto monopoly position for years, which buys it the time to make the vertical integration work, and uniquely positions it to unlock that technology faster than anyone else.

“Output > method” Vertical Integrators (option #1) tend to start compounding earlier in their lifecycle and for longer durations than the more method-obsessed companies, and therefore result in much larger outcomes - more suitable for venture-backable exits.

At the same time, building a compounding technology moat is critical to ensure long-term market dominance and higher valuation premiums when it comes to returns for the investors & founders. Building a technical moat doesn't necessarily mean patentable IP, but similar to vertical SaaS lies in rapidly productising unique insight in a complex domain.

The art lies in balancing complexity - taking on enough technical and operational depth to build defensibility, but not so much that you drown in it. Output over method is a spectrum, where some technical innovation is necessary to draw moats, but too much from day 1 will get you stuck. The best teams move fast, can deal with immense complexity, and iterate relentlessly - compounding through execution rather than invention alone.

Addressing the Labor Constraint

A key constraint to scaling output in real-world infrastructure is skilled labor and tacit knowledge. Tech startups, and vertical integrators specifically, can leverage software and AI to give skilled workers like machinists and engineers superpowers, thereby drastically reducing the headcount to run and scale their facilities - one skilled worker runs what took five.

Over time, they leverage their domain-specific, context aware, proprietary AI models to increasingly lower the expertise required and move towards unskilled labor - swapping four-year apprenticeship programs for 2-week crash courses.

The final step, once unskilled worker productivity taps out, they swap bodies for bots to drive the degree of automation on the shop floor and autonomous AI agents for knowledge work. Note that this is the last step, only after the vertical integrator has mapped the value chain in detail, collected immense amounts of data and trained highly reliable models on the back of it.

Vertical integration isn't just about hardware - it's the only way to collect the deep industrial knowledge that makes labor a virtually infinite resource at near-zero marginal cost and unlocks non-linear scaling for techno-industrials.

Underestimated TAM for Vertical Integrators

A key advantage of the VI and difference to pure SaaS is the spend the company is going after.

A SaaS startup is going after the available software spend of an incumbent, and can - at times - unlock larger software spend by showing clear ROI cases.

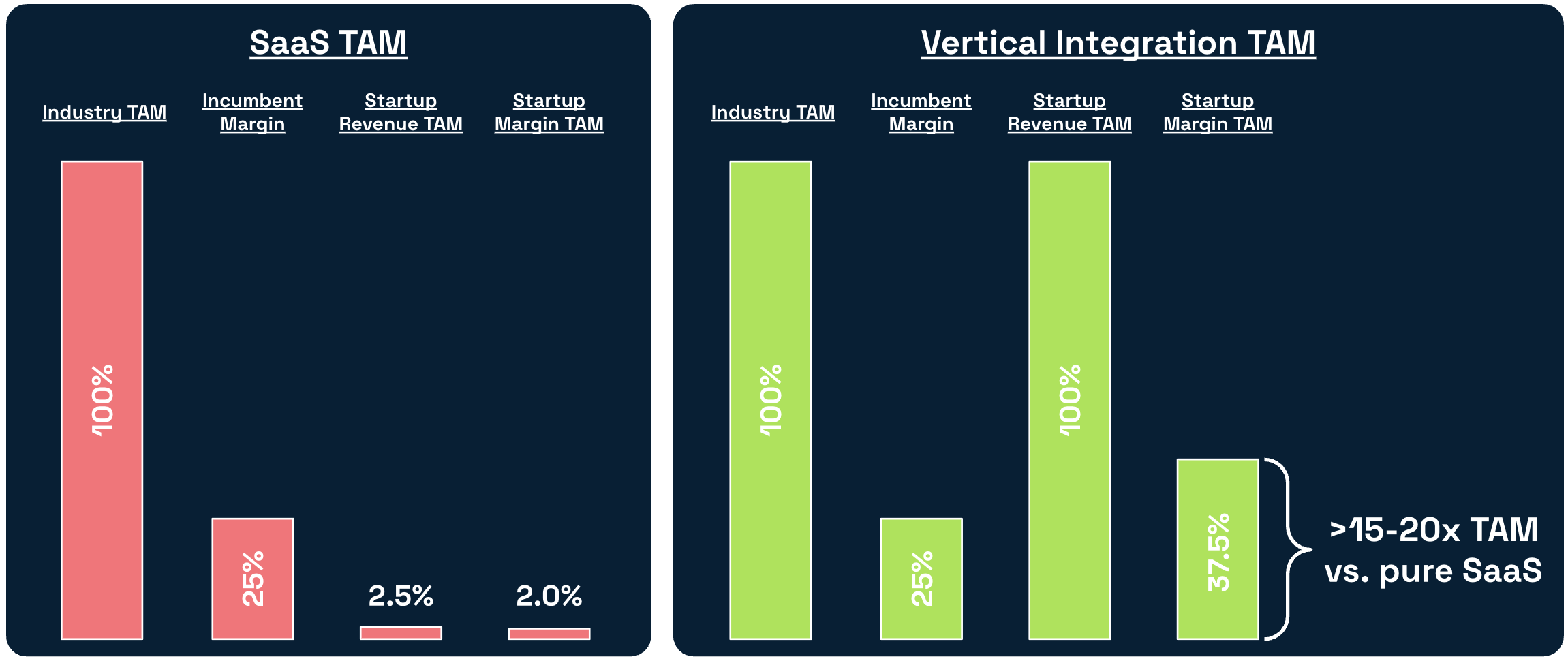

Let’s take a hypothetical example of an industrial company, operating in a $100bn TAM (i.e. annual revenue opportunity for the incumbent), where the incumbent operates on a 25% gross margin. Let’s assess the actual revenue TAM value capture opportunity for a startup in this market using SaaS vs Vertical Integration:

SaaS example: A truly game-changing vertical SaaS suite, might be able to justify capturing 10% of the incumbent’s gross profit as SaaS license fee, which is 2.5% of the top-line revenue, and with typical 80% SaaS margin, the actual value capture opportunity in terms of gross profit for the SaaS company is 2% of the revenue TAM.

Vertical Integrator example: The VI goes after the same industry spend as the incumbent, so the revenue TAM of the VI is equal to the revenue TAM of the incumbent. The VI operates below the 80% gross margin of the SaaS company, but above the gross margin of the incumbent. By leveraging state of the art technologies across the value chain and building a much leaner, more automated infrastructure, the VI can increase the gross margin from 25% (incumbent benchmark) by, let’s assume, a relative 50% to 37.5%.

In this hypothetical example the VI’s 37.5% gross profit TAM (as % of total revenue TAM) is >15-20-times larger than the SaaS company’s 2% gross profit TAM (as % of total revenue TAM).

Source: Own Illustration

That being said, there’s a bit more nuance required, rather than comparing these metrics side-by-side:

Market penetration velocity: A VI can capture unmet demand almost instantly and then win share from incumbents over time by outperforming them on cost, reliability, or speed. SaaS firms often face fewer adoption hurdles in theory, but only in true greenfield markets. In practice, they’re often displacing entrenched systems like ERPs or require a change of organizational habits, with enterprise sales cycles that stretch 12+ months. Ironically, VIs often unlock larger budgets faster, since their pitch is empirical (“we’ll deliver your existing parts faster and cheaper”) rather than transformational (“please replace your core system and change the way you work”).

Supply-side scaling: One clear benefit of SaaS is its near-zero marginal distribution cost, i.e. spinning up another instance of the SaaS product for a new customer can happen immediately vs the VI having to build additional physical supply-side capacity to produce more. Although for enterprise deployments in legacy industries, the marginal distribution cost of SaaS is far from zero - customers often require custom features or solution engineering, comprehensive training and support, custom implementation/integration, etc.

The above leads me to the conclusion that the vast majority of enterprise value in the real-world domain will be captured by vertical integrators rather than pure-SaaS companies or innovators on method.

The moat of the vertical integrator is the integration. Starting with iteratively building unique insight and expertise along the value chain and combining proven technologies. Then increasingly drawing moats by collecting domain-specific datasets, training their own narrow AI models and with scale starting to innovate on method, as well as leveraging economies of scale. Ultimately resulting in unassailable industrial monopolies, who rapidly compound and continue to do so for decades.

Next chapter: Laying out some of the key foundational technologies underpinning real-world vertical integrators and the adoption flywheel that enables them to scale rapidly.